The Five Major Causes of Mass Murder in America – A Three Part Series – Part Two: The Lack of Proper Mental Health Care : A Well Thought Out Scream by James Riordan

After much detailed research for a book I am writing entitled Ready to Pop : The Rise of Mass Murder in America, I have come to the conclusion that there are five factors in America today which have combined into a perfect storm to fuel mass murder including school shootings. A single factor applies to a greater or lesser degree depending upon the age of the shooter. These factors are : Access to Guns, Familiarity with Violence, The Pressure of Consumerism, The Lack of Proper Mental Health Treatment and The Culture of Fame. Last week we examined Access to Guns and The Familiarity with Violence. This week we will look at Part Two : The Lack of Proper Mental Health Treatment.

PART TWO : The Lack of Proper Mental Health Treatment

There were more school shootings this week and more mass murders and it is my belief that there will be more every week until we find a way to address the five primary causes which I listed above. By most people’s standards, anyone who commits mass murder is mentally ill. Whether or not they knew what they were doing and were therefore accountable by our legal system is another question entirely, but no one is debating that there is something mentally wrong with a man who rents out a room in a hotel and then proceeds to kill fifty strangers. To examine why America has more mass murders than any other country, we must include a discussion of the mental health system.

There were more school shootings this week and more mass murders and it is my belief that there will be more every week until we find a way to address the five primary causes which I listed above. By most people’s standards, anyone who commits mass murder is mentally ill. Whether or not they knew what they were doing and were therefore accountable by our legal system is another question entirely, but no one is debating that there is something mentally wrong with a man who rents out a room in a hotel and then proceeds to kill fifty strangers. To examine why America has more mass murders than any other country, we must include a discussion of the mental health system.

The programs and policies that resulted in the release of most of the nation’s mentally ill patients from the hospital to the community are now widely regarded as a major failure. A recent report from the American Psychiatric Association, included sweeping critiques of the policy and spread the blame everywhere, faulting politicians, civil libertarian lawyers and psychiatrists. The question remains how did this happen and who played the key roles in the formation of this ill-fated policy? What motivated these influential people and what lessons are to be learned? There is no question that the people who created this policy were running scared from rising costs and a bleak estimation of future expenditures. That was their first mistake. But ultimately, the conjectures that led to such dismal failures were based on a totally unrealistic belief in the effectiveness of modern drug therapy. Many psychiatrists involved as practitioners and policy makers in the 1950’s and 1960’s have said in the interviews that heavy responsibility lay on a sometimes neglected aspect of the problem: the overreliance on drugs to do the work of society. The records show that the politicians were dogged by the image and financial problems posed by the state hospitals and that the scientific and medical establishment sold Congress and the state legislatures a quick fix for a complicated problem that was bought sight unseen.

In California, for example, the number of patients in state mental hospitals reached a peak of 37,500 in 1959 when Edmund G. Brown was Governor, fell to 22,000 when Ronald Reagan attained that office in 1967, and continued to decline under his administration and that of his successor, Edmund G. Brown Jr. The senior Mr. Brown now expresses regret about the way the policy started and ultimately evolved. ”They’ve gone far, too far, in letting people out,” he said in an interview. Dr. Robert H. Felix, who was then director of the National Institute of Mental Health and a major figure in the shift to community centers, says now on reflection: ”Many of those patients who left the state hospitals never should have done so. We psychiatrists saw too much of the old snake pit saw too many people who shouldn’t have been there and we overreacted. The result is not what we intended, and perhaps we didn’t ask the questions that should have been asked when developing a new concept, but psychiatrists are human, too, and we tried our damnedest.”

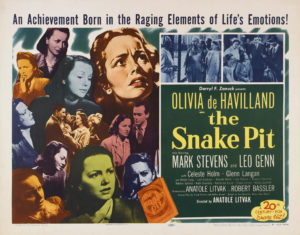

Snake Pit was a popular movie released in 1948, directed by Anatole Litvak and starring Olivia de Havilland as a woman unjustly committed to an asylum and the horrible practices shown in the film were widely embraced by the public as the truth (some of them were).

Dr. John A. Talbott, president of the American Psychiatric Association, said, ”The psychiatrists involved in the policy making at that time certainly oversold community treatment, and our credibility today is probably damaged because of it.” He said the policies ”were based partly on wishful thinking, partly on the enormousness of the problem and the lack of a silver bullet to resolve it, then as now.”

The original policy changes were backed by scores of national professional and philanthropic organizations and several hundred people prominent in medicine, academia and politics. The belief then was widespread that the same scientific researchers who had conjured up antibiotics and vaccines during the outburst of medical discovery in the 50’s and 60’s had also developed penicillins to cure psychoses and thus revolutionize the treatment of the mentally ill. And these leaders were prodded into action by a series of scientific studies in the 1950’s purporting to show that mental illness was far more prevalent than had previously been believed.

Finally, there was a growing economic and political liability faced by state legislators. Enormous amounts of tax revenues were being used to support the state mental hospitals, and the institutions themselves were increasingly thought of as ”snake pits” or facilities that few people wanted.

One of the most influential groups in bringing about the new national policy was the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health, an independent body set up by Congress in 1955. One of its two surviving members, Dr. M. Brewster Smith, a University of California psychologist who served as vice president, said the commission took the direction it did because of ”the sort of overselling that happens in almost every interchange between science and government.”

”Extravagant claims were made for the benefits of shifting from state hospitals to community clinics,” Dr. Smith said. ”The professional community made mistakes and was overly optimistic, but the political community wanted to save money.”

Charles Schlaifer, a New York advertising executive who served as secretary-treasurer of the group, said he was now disgusted with the advice presented by leading psychiatrists of that day. ”Tranquilizers became the panacea for the mentally ill,” he said. ”The state programs were buying them by the carload, sending the drugged patients back to the community and the psychiatrists never tried to stop this. Local mental health centers were going to be the greatest thing going, but no one wanted to think it through.”

Dr. Bertram S. Brown, a psychiatrist and Federal official who was instrumental in shaping the community center legislation in 1963, agreed that Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson were to some extent misled by the mental health community and Government bureaucrats. ”The bureaucrat-psychiatrists realized that there was political and financial overpromise,” he said.

Dr. Brown, then an executive of the National Institute of Mental Health and now president of Hahnemann University in Philadelphia, stated candidly in an interview: ”Yes, the doctors were overpromising for the politicians. The doctors did not believe that community care would cure schizophrenia, and we did allow ourselves to be somewhat misrepresented.”

”They ended up with everything but the kitchen sink without the issue of long-term funding being settled,” he said. ”That was the overpromising.”

Dr. Brown said he and the other architects of the community centers legislation believed that while there was a risk of homelessness, that it would not happen if Federal, state, local and private financial support ”was sufficient” to do the job.

The legislation sought to create a nationwide network of locally based mental health centers which, rather than large state hospitals, would be the main source of treatment. The center concept was aided by Federal funds for four and a half years, after which it was hoped that the states and local governments would assume responsibility. ”We knew that there were not enough resources in the community to do the whole job, so that some people would be in the streets facing society head on and questions would be raised about the necessity to send them back to the state hospitals,” Dr. Brown said. But, he continued, ”It happened much faster than we foresaw.” The discharge of mental patients was accelerated in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s in some states as a result of a series of court decisions that limited the commitment powers of state and local officials.

Dr. Brown insists, as do others who were involved in the Congressional legislation to establish community mental health centers, that politicians and health experts were carrying out a public mandate to abolish the abominable conditions of insane asylums. He and others note – and their critics do not disagree – that their motives were not venal and that they were acting humanely. In retrospect it does seem clear that questions were not asked that might have been asked. In the thousands of pages of testimony before Congressional committees in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, little doubt was expressed about the wisdom of deinstitutionalization. And the development of tranquilizing drugs was regarded as an unqualified ”godsend,” as one of the nation’s leading psychiatrists, Dr. Francis J. Braceland, described it when he testified before a Senate subcommittee in 1963.

Dr. Brown insists, as do others who were involved in the Congressional legislation to establish community mental health centers, that politicians and health experts were carrying out a public mandate to abolish the abominable conditions of insane asylums. He and others note – and their critics do not disagree – that their motives were not venal and that they were acting humanely. In retrospect it does seem clear that questions were not asked that might have been asked. In the thousands of pages of testimony before Congressional committees in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, little doubt was expressed about the wisdom of deinstitutionalization. And the development of tranquilizing drugs was regarded as an unqualified ”godsend,” as one of the nation’s leading psychiatrists, Dr. Francis J. Braceland, described it when he testified before a Senate subcommittee in 1963.

Dr. Braceland, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association who is a retired professor of psychiatry at Yale University, still maintains, however, that under the circumstances the widespread prescription of drugs for the mentally ill was and is a wise policy. ”We had no alternative to the use of drugs for schizophrenia and depression,” Dr. Braceland said. ”Before the introduction of drugs like Thorazine we never had drugs that worked. These are wonderful drugs and they kept a lot of people out of the hospitals.”

His point is borne out repeatedly by references in Congressional testimony, such as the following exchange at a House subcommittee hearing between Representative Leo W. O’Brien, Democrat of upstate New York, and Dr. Henry N. Pratt, director of New York Hospital in Manhattan, who appeared on behalf of the American Hospital Association.

Mr. O’Brien: ”Do you know offhand how much New York appropriates annually for its mental hospitals?”

Dr. Pratt: ”It is the vast sum of $400 million to $500 million.”

Mr. O’Brien: ”So you see that, through a real attempt to handle this problem at the community level, the possibility that this dead weight of $400 million to $500 million a year around the necks of the New York State taxpayers might be reduced considerably in the next 15 or 20 years?

Dr. Pratt: ”I do, indeed. Yes, sir.”

He then told the subcommittee that ”striking proof of the advantages of local short-term intensive care of the mentally ill was brought out” in a Missouri study.

Dr. Pratt’s testimony and the Missouri study were repeatedly cited in subsequent Congressional debates on the community centers bill by such politicians as Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota and Representative Kenneth A. Roberts of Alabama. The Missouri study, which compared a group of 412 patients in two intensive treatment centers with patients admitted to five mental hospitals, showed that the average stays for patients in the large hospitals were 237 days longer than for similarly diagnosed patients at the treatment centers. But Dr. George A. Ulett of St. Louis, the psychiatrist who directed the study as head of Missouri’s Division of Mental Diseases, now says the numbers cited, though correct, were misinterpreted. ”We did have dramatic numbers, but the initial success of the community centers in Missouri hinged on the large numbers of psychiatrists and support personnel who staffed the centers at that time,” Dr. Ulett said.

The centers were two pilot projects that were given special staff and attention to demonstrate what could be accomplished, he said. By linking the community centers to large teaching hospitals in major cities and providing adequate funds for their maintenance it was possible to attract the quality of staff that all but guaranteed better results than the old state hospitals, he said. ”Unfortunately,” he said, ”over the years the budgets were progressively reduced, the professional staffs were cut, and the program regressed to right back where it started.”

Dr. Frank R. Lipton and Dr. Albert Sabatini of Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital in Manhattan, who have done research on the problems of the homeless, say one of the major flaws in the concept of deinstitutionalization was the notion that serious, chronic mental disorders could be minimized, if not totally prevented, through care provided within the local community. ”This philosophical and ideological shift in thinking was not adequately validated, yet it became one of the major conceptual bases for moving the locus of care,” they said in a recent study.

Dr. Frank R. Lipton and Dr. Albert Sabatini of Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital in Manhattan, who have done research on the problems of the homeless, say one of the major flaws in the concept of deinstitutionalization was the notion that serious, chronic mental disorders could be minimized, if not totally prevented, through care provided within the local community. ”This philosophical and ideological shift in thinking was not adequately validated, yet it became one of the major conceptual bases for moving the locus of care,” they said in a recent study.

Some problems have actually been brought on for mental patients by long-term use of drugs. This condition has been considered by Dr. Loren Mosher of the Uniformed Services Medical University in Bethesda, Md., who says that from 15 percent to 40 percent of such mental patients develop uncontrollable movements of the mouth and neck that can only be cured by taking people off the drugs. The consensus seems to be that the more intelligent approach to the overall problem is to realize both the limitations and value of the drugs, the importance of combining drug treatment with proper care – either in hospitals or local clinics, depending on the individual case – and that mental illness is a sociological fact that cannot be ignored simply out of a desire to save tax dollars.

Jack R. Ewalt, who directed the staff of the Joint Commission when it was founded in 1955, says now that he remains ”a great believer in the use of drugs, but they are just another treatment, not a magic.” ”Drugs can help people get back to the community,” he said, ”but they have to have medical care, a place to live and someone to relate to. They can’t just float around aimlessly.”

Dr. Ewalt said the 1963 act was supposed to have the states continue to take care of the mentally ill but that many states simply gave up and ceded most of their responsibility to the Federal Government. ”The result was like proposing a plan to build a new airplane and ending up only with a wing and a tail,” Dr. Ewalt said. ”Congress and the state governments didn’t buy the whole program of centers, plus adequate staffing, plus long-term financial supports.”

The failure of the program can be easily seen in any major city. In Washington D.C., Joggers trot along freshly paved paths, and sunbathers stretch out on the manicured grass of Georgetown Waterfront Park in Washington. Nearby but oblivious to most, Janice lines up six garbage bags swollen with soiled blankets and clothes on a stretch of sidewalk where she sleeps each night. “I’m not homeless,” she says when asked how long she’s been living on the streets. “I’m waiting for the movie star.”

More than 124,000 – or one-fifth – of the 610,000 homeless people across the USA suffer from a severe mental illness, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. They’re gripped by schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or severe depression — all manageable with the right medication and counseling but debilitating if left untreated. In the absence of such care, their plight costs the federal government millions of dollars a year in housing and services and prolongs their disorders.

As they cycle between street corner, jail cell and hospital bed, the homeless who are mentally ill cost local, state and federal agencies millions of dollars a year. This fiscal year, the federal government will spend $5 billion on programs for the homeless. Next year, that figure is likely to grow to nearly $5.7 billion.

Sam Tsemberis, executive director of Pathways to Housing, a New York-based housing group that works in cities across the USA, says the ability to house people like Edwards comes not just from new housing strategies but from a fundamental shift in how Americans view people with mental illness. As a homeless specialist at New York’s Bellevue Hospital in the late 1980s, Tsemberis witnessed firsthand the seemingly endless stream of mentally ill patients who visited the hospital’s emergency room before returning to the streets. He began recording how patients with schizophrenia, given proper housing and treatment, were able to hold jobs, manage their bills and cook their own meals, and he encouraged advocates to house first, treat later. “We have misunderstood profoundly what it means to be mentally ill,” he says. “They’re capable of far more than we ever imagined.”

Slowly, the rest of the country caught on. Tsemberis helped popularize the Housing First initiative that led to permanent-supportive housing. Officials in Houston and surrounding Harris County decided not to wait for more federal help. Faced with a growing chronic homeless population and diminishing federal aid, officials from the Houston Housing Authority, Houston Police Department and other agencies joined forces in 2011 to create a computerized countywide housing-first network that helps place chronic homeless people in apartments quickly. It’s become a model across the USA.

In November 1980, Republican Ronald Reagan overwhelmingly defeated Jimmy Carter, who received less than 42% of the popular vote, for president. Republicans took control of the Senate (53 to 46), the first time they had dominated either chamber since 1954. Although the House remained under Democratic control (243 to 192), their margin was actually much slimmer, because many southern “boll weevil” Democrats voted with the Republicans.

One month prior to the election, President Carter had signed the Mental Health Systems Act, which had proposed to continue the federal community mental health centers program, although with some additional state involvement. Consistent with the report of the Carter Commission, the act also included a provision for federal grants “for projects for the prevention of mental illness and the promotion of positive mental health,” an indication of how little learning had taken place among the Carter Commission members and professionals at NIMH. With President Reagan and the Republicans taking over, the Mental Health Systems Act was discarded before the ink had dried and the CMHC funds were simply block granted to the states. The CMHC program had not only died but been buried as well. An autopsy could have listed the cause of death as naiveté complicated by grandiosity.

President Reagan never understood mental illness. Like Richard Nixon, he was a product of the Southern California culture that associated psychiatry with Communism. Two months after taking office, Reagan was shot by John Hinckley, a young man with untreated schizophre-nia. Two years later, Reagan called Dr. Roger Peele, then director of St. Elizabeths Hospital, where Hinckley was being treated, and tried to arrange to meet with Hinckley, so that Reagan could forgive him. Peele tactfully told the president that this was not a good idea. Reagan was also exposed to the consequences of untreated mental illness through the two sons of Roy Miller, his personal tax advisor. Both sons developed schizophrenia; one committed suicide in 1981, and the other killed his mother in 1983. Despite such personal exposure, Reagan never exhibited any interest in the need for research or better treatment for serious mental illness.

California has traditionally been on the cutting edge of American cultural developments, with Anaheim and Modesto experiencing changes before Atlanta and Moline. This was also true in the exodus of patients from state psychiatric hospitals. Beginning in the late 1950s, California became the national leader in aggressively moving patients from state hospitals to nursing homes and board-and-care homes, known in other states by names such as group homes, boarding homes, adult care homes, family care homes, assisted living facilities, community residential facilities, adult foster homes, transitional living facilities, and residential care facilities. Hospital wards closed as the patients left. By the time Ronald Reagan assumed the governorship in 1967, California had already deinstitutionalized more than half of its state hospital patients. That same year, California passed the landmark Lanterman-Petris-Short (LPS) Act, which virtually abolished involuntary hospitalization except in extreme cases. Thus, by the early 1970s California had moved most mentally ill patients out of its state hospitals and, by passing LPS, had made it very difficult to get them back into a hospital if they relapsed and needed additional care. California thus became a canary in the coal mine of deinstitutionalization.

The results were quickly apparent. As early as 1969, a study of California board-and-care homes described them as follows: These facilities are in most respects like small long-term state hospital wards isolated from the community. One is overcome by the depressing atmosphere. . . . They maximize the state-hospital-like atmosphere. . . . The operator is being paid by the head, rather than being rewarded for rehabilitation efforts for her “guests.”

The study was done by Richard Lamb, a young psychiatrist working for San Mateo County; in the intervening years, he has continued to be the leading American psychiatrist pointing out the failures of deinstitutionalization.

By 1975 board-and-care homes had become big business in California. In Los Angeles alone, there were “approximately 11,000 ex-state-hospital patients living in board-and-care facilities.” Many of these homes were owned by for-profit chains, such as Beverly Enterprises, which owned 38 homes. Many homes were regarded by their owners “solely as a business, squeezing excessive profits out of it at the expense of residents.” Five members of Beverly Enterprises’ board of directors had ties to Governor Reagan; the chairman was vice chairman of a Reagan fundraising dinner, and “four others were either politically active in one or both of the Reagan [gubernatorial] campaigns and/or contributed large or undisclosed sums of money to the campaign.” Financial ties between the governor, who was emptying state hospitals, and business persons who were profiting from the process would also soon become apparent in other states.

Many of the board-and-care homes in California, as elsewhere, were clustered in city areas that were rundown and thus had low rents. In San Jose, for example, approximately 1,800 patients discharged from nearby Agnews State Hospital were placed in homes clustered near the campus of San Jose State University. As early as 1971 the local newspaper decried this “mass invasion of mental patients.” Some patients left their board-and-care homes because of the poor living conditions, whereas others were evicted when the symptoms of their illness recurred because they were not receiving medication, but both scenarios resulted in homelessness. By 1973 the San Jose area was described as having “discharged patients…living in skid row…wandering aimlessly in the streets . . . a ghetto for the mentally ill and mentally retarded.”

Los Angeles County Jail

Similar communities were becoming visible in other California cities as well as in New York. In Long Beach on Long Island, old motels and hotels were filled with patients discharged from nearly Creedmore and Pilgrim State Hospitals. By 1973, community residents were complaining that their town was becoming a psychiatric ghetto; at the local Catholic church, patients were said to “have urinated on the floor during Mass and eaten the altar flowers.” The Long Beach City Council therefore passed an ordinance requiring patients to take their prescribed medication as a condition for living there. Predictably, the New York Civil Liberties Union immediately challenged the ordinance as being unconstitutional, and it was so ruled. By this time, there were about 5,000 board-and-care homes in New York City, some with as many as 285 beds and with up to 85% of their residents having been discharged from the state hospitals. As one New York psychiatrist summarized the situation: “The chronic mentally ill patient has had his locus of living and care transferred from a single lousy institution to multiple wretched ones.”

Until the 1980s, most people in the United States were unaware that the deinstitutional-ization of patients from state mental hospitals was going terribly wrong. Some were aware that homicides and other untoward things were happening in California, but such things were to be expected, because it was, after all, California. President Carter’s Commission on Mental Health issued its 1978 report and recommended doing more of the same things—more CMHCs, more prevention of mental illness, and more federal spending. The report gave no indication of a pending crisis. The majority of patients who had been discharged from state hospitals in the 1960s and 1970s had gone to their own homes, nursing homes, or board-and-care homes; they were, therefore, out of sight and out of mind.

In the 1980s, this all changed. Deinstitutionalization became, for the first time, a topic of national concern. The beginning of the discussion was heralded by a 1981 editorial in the New York Times that labeled deinstitutionalization “a cruel embarrassment, a reform gone terribly wrong.” Three years later, the paper added: “The policy that led to the release of most of the nation’s mentally ill patients from the hospital to the community is now widely regarded as a major failure.” During the following decade, there were increasing concerns publicly expressed about mentally ill individuals in nursing homes, board-and-care homes, and jails and prisons. There were also periodic headlines announcing additional high-profile homicides committed by individuals who were clearly psychotic. But the one issue that took center stage in the 1980s, and directed public attention to deinstitutionalization, was the problem of mentally ill homeless persons.

During the 1980s, an additional 40,000 beds in state mental hospitals were shut down. The patients being sent to community facilities were no longer those who were moderately well-functioning or elderly; rather, they included the more difficult, chronic patients from the hospitals’ back wards. These patients were often younger than patients previously discharged, less likely to respond to medication, and less likely to be aware of their need for medication. In 1988 the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) issued estimates of where patients with chronic mental illness were living. Approximately 120,000 were said to be still hospitalized; 381,000 were in nursing homes; between 175,000 and 300,000 were living in board-and-care homes; and between 125,000 and 300,000 were thought to be homeless. These broad estimates for those living in board-and-care homes and on the streets suggested that neither NIMH nor anyone else really knew how many there were.

Cook County Jail

Abuse of mentally ill persons in nursing homes had originally come to public attention during 1974 hearings of the Senate Committee on Aging. Those hearings had described nursing homes actually bidding on patients in attempts to get those who were most easily managed; bounties of $100 paid by nursing homes to hospital psychiatrists for every patient sent to them; and exorbitant profits for the nursing homes. As a consequence of such hearings and a 1986 study of nursing homes by the Institute of Medicine, Congress passed legislation in 1987 requiring all Medicaid-funded nursing homes to screen new admissions to keep out patients who did not qualify for admission because they did not require skilled nursing care. Follow-up studies indicated that the screening mandate had little effect on admission policies or abuses.

Sociologist Andrew Scull in 1981 summarized the economics of the board-and-care industry: “The logic of the marketplace suffices to ensure that the operators have every incentive to warehouse their charges as cheaply as possible, since the volume of profit is inversely proportional to the amount expended on the inmates.” In addition, because many board-and-care homes were in crime-ridden neighborhoods, mentally ill individuals living in them were often victimized when they went outside. A 1984 study of 278 patients living in board-and-care homes in Los Angeles reported that one-third “reported being robbed and/or assaulted during the preceding year.”

Mental Illness & The Homeless

The problems of mentally ill individuals in nursing homes and board-and-care homes rarely elicited media attention in the 1980s. By contrast, the problem of homeless persons, including the mentally ill homeless, became a major story. In Washington, Mitch Snyder and the National Coalition for the Homeless burst onto the national scene by staging hunger strikes and sleep-ins on sidewalk grates. Their message was that homeless persons are just like you and me and all they need is a house and a job. Snyder challenged President Reagan, accusing him of being the main cause of homelessness, and the media extensively covered the controversy. By the time Snyder committed suicide in 1990, homelessness had become a major topic of national discussion.

Despite the claims of homeless advocates, media attention directed to homeless persons made it increasingly clear that many of them were, in fact, seriously mentally ill. In 1981, Life magazine ran a story titled “Emptying the Madhouse: The Mentally Ill Have Become Our Cities’ Lost Souls.” In 1982, Rebecca Smith froze to death in a cardboard box on the streets of New York; the media focused on her death because it was said that she had been valedictorian of her college class before becoming mentally ill. In 1983, the media covered the story of Lionel Aldridge, the former all-pro linebacker for the Green Bay Packers; after developing schizophrenia, he had been homeless for several years on the streets of Milwaukee. In 1984, a study from Boston reported that 38% of homeless persons in Boston were seriously mentally ill. The report was titled “Is Homelessness a Mental Health Problem?” and confirmed what people were increasingly beginning to suspect—that many homeless persons had previously been patients in the state mental hospitals.

By the mid-1980s, a consensus had emerged that the total number of homeless persons was increasing. The possible reasons for this increase became a political football, but the failure of the mental health system was one option widely discussed. A 1985 report from Los Angeles estimated that 30% to 50% of homeless persons were seriously mentally ill and were being seen in “ever increasing numbers.” The study concluded that this was “in part the product of the deinstitutionalization movement….The ‘Streets’ have become ‘The Asylums’ of the 80s.”

By the end of the 1980s, the origins of the increasing number of mentally ill homeless persons had become abundantly clear. A study of 187 patients discharged from Metropolitan State Hospital in Massachusetts reported that 27% had become homeless. A study of 132 patients discharged from Columbus State Hospital in Ohio reported that 36% had become homeless. In 1989, when a San Francisco television station wished to advertise its series on homelessness, it put up posters around the city saying, “You are now walking though America’s newest mental institution.” Psychiatrist Richard Lamb added: “Probably nothing more graphically illustrates the problems of deinstitutionalization than the shameful and incredible phenomenon of the homeless mentally ill.”

Mental Illness & the Justice System

At the same time that mentally ill homeless persons were becoming an object of national concern during the 1980s, the number of mentally ill persons in jails and prisons was also increasing. A 1989 review of available studies concluded that “the prevalence rates for major psychiatric disorders . . . [in jails and prisons] have increased slowly and gradually in the last 20 years and will probably continue to increase.” Various studies reported rates ranging from 6% (Virginia) and 8% (New York) to 10% (Oklahoma and California) and 11% (Michigan and Pennsylvania). By 1990, a national survey concluded: Given all the data, it seems reasonable to conclude that approximately 10 percent of inmates in prisons and jails, or approximately 100,000 individuals, suffer from schizophrenia or manic-depressive psychosis [bipolar disorder]. This 10% estimate contrasted with the 5% prevalence rate that had been widely cited a decade earlier.

As more and more mentally ill individuals entered the criminal justice system in the 1980s, local police and sheriffs’ departments were increasingly affected. In New York City, calls associated with “emotionally disturbed persons,” referred to as “EDPs,” increased from 20,843 in 1980 to 46,845 in 1988, and “experts say similar increases have occurred in other large cities.” Many such calls required major deployments of police resources. The rescue of a mentally ill man from the top of a tower on Staten Island, for example, “required at least 20 police officers and supervisors, half a dozen emergency vehicles, several highway units and a helicopter.” In an attempt to deal with these psychiatric emergencies, the police department in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1988 created the first specially trained police Crisis Intervention Team, or CIT, as it would become known as it was replicated in other cities.

California was the first state to witness not only an increase in homelessness associated with deinstitutionalization but also an increase in incarceration and episodes of violence. In 1972 Marc Abramson, another young psychiatrist working for San Mateo County, published a landmark paper entitled “The Criminalization of Mentally Disordered Behavior.” Abramson claimed that because the new LPS statute made it difficult to get patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital, police “regard arrest and booking into jail as a more reliable way of securing involuntary detention of mentally disordered persons.” Abramson quoted a California prison psychiatrist who claimed to be “literally drowning in patients. . . . Many more men are being sent to prison who have serious mental problems.” Abramson’s paper was the first clear description of the increase of mentally ill persons in jails and prisons, an increase that would grow markedly in subsequent years.

Is there any way to estimate the frequency of episodes of violence committed by mentally ill people who were not being treated? There was then, and continues to be, no national database that tracks homicides committed by mentally ill persons. However, a small study published in 1988 provided a clue. In Contra Costa County, California, all 71 homicides committed between 1978 and 1980 were examined. Seven of the 71 homicides were found to have been done by individuals with schizophrenia, all of whom had been previously hospitalized at some point before the crime. The 10% rate was also consistent with the findings of another small study in Albany County, New York. Therefore, by the late 1980s, it appeared that violent acts committed by untreated mentally ill persons was one of the consequences of the deinstitutionalization movement, and the problem appeared to be a growing one.

By the mid-1970s, studies in some states suggested that about 5% of jail inmates were seriously mentally ill. A study of five California county jails reported that 6.7% of the inmates were psychotic. A study of the Denver County Jail reported that 5% of prisoners had a “functional psychosis.” Such figures contrasted with studies from the 1930s that had reported less than 2% of jail inmates as being seriously mentally ill. In 1973 the jail in Santa Clara County, which included San Jose, “created a special ward…to house just the individuals who have such a mental condition”; this was apparently the first county jail to create a special mental illness unit. Given the increasing number of seriously mentally ill individuals living in the community in California by the mid-1970s, it is not surprising to find that they were impacting the tasks of police officers. A study of 301 patients discharged from Napa State Hospital between 1972 and 1975 found that 41% of them had been arrested. According to the study, “patients who entered the hospital without a criminal record were subsequently arrested about three times as often as the average citizen.” Significantly, the majority of these patients had received no aftercare following their hospital discharge. By this time, police in other states were also beginning to feel the burden of the discharged, but often untreated, mentally ill individuals. In suburban Philadelphia, for example, “mental-illness-related incidents increased 227.6% from 1975 to 1979, whereas felonies increased only 5.6%.”

Today, in 2017, the two facilities in America that house the most mental patients are the Los Angele County Jail in California and the Cook County Jail in Illinois. In America more mental patients go to prison than to a mental hospital.

NEXT WEEK: The Five Major Causes of Mass Murder in America : PART THREE : The Pressure of Consumerism and The Culture of Fame.

No Comment