Star Wars’ Is Really About Feminism. And Jesus: Cass Sunstein

published May 31st 2016, 10:30 am, by Cass R Sunstein

(Bloomberg View) —

Thirty-nine years ago, on May 25, 1977, a movie was released with a somewhat ridiculous name: “Star Wars.” (It’s now called “Episode IV: A New Hope.”) Almost no one thought that it would do well, and nobody could have predicted it would become the defining saga of our era. How did it manage to do that?

One answer is that like a great novel or poem, Star Wars doesn’t tell you what to think. You can understand it in different, even contradictory ways. Here are six of those ways.

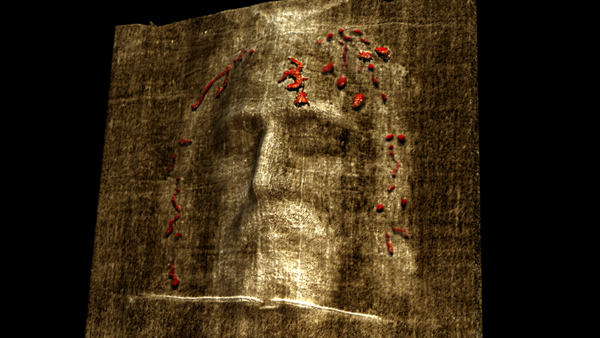

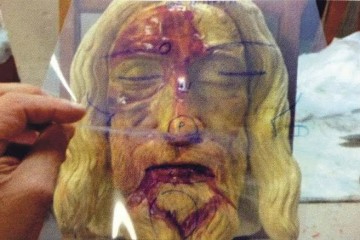

Christianity

Anakin Skywalker is the product of a virgin birth. He has no human father. He turns out to be a Christ-like figure, dying for humanity’s sins, which he incarnates and symbolizes. Star Wars is an imaginative reconstruction of Jesus’s life, in which the Jesus figure is the sinner — unable to resist Satan until the very end, when he sacrifices everything for his child, and symbolically for all children.

In Star Wars, it is the promise of immortality (for his loved ones) that turns out to be Satan’s apple. That’s how Emperor Palpatine, the saga’s serpent, seduces Anakin, convincing him to give up his very soul. So there’s a Faustian bargain here as well. But in sacrificing his own life, Anakin defeats the great tempter — and gets his soul back in the process. Loving his son and killing Satan, he restores peace on earth. It’s no accident that the word peace appears in the crawl in both “A New Hope” and “The Force Awakens.” And Christ is of course the Redeemer.

Oedipus Jedi

Perhaps Star Wars is best understood as something very different, a deeply Oedipal story about fathers, sons and unavailable mothers. Freud is the right resource, not the Bible.

Fatherless Anakin is in desperate search for some kind of strong paternal figure, about whom he is inevitably ambivalent. First it is Qui-Gon, then it is Obi-Wan, and finally the Emperor. Anakin, the symbolic son, turns out to be responsible for the death of the first and the third — and he tries mightily to kill the second. He falls for Padmé, who is a lot older than he is and unquestionably a maternal figure. “You’re a funny little boy,” she says on first meeting him. “Annie, you’ll always be that little boy I met on Tatooine,” Padmé later says after a long absence, when he’s all grown. Isn’t that exactly how mothers think about their boys? And he gets to sleep with her!

Anakin’s path to the Dark Side begins only when his real mother is killed. In some sense, he’s in love with her. Aren’t all sons in love with their mothers? On this view, the Tragedy of Darth Vader is a complex and psychologically acute (if somewhat disturbing) reworking of Sophocles’ tale.

Feminism

From the feminist point of view, is Star Wars awful and kind of embarrassing, or actually terrific and inspiring? No one can doubt that “The Force Awakens” strikes a strong blow for sex equality: Rey is the unambiguous hero (the new Luke!), and she gets to kick some Dark Side butt. Just look at the expression on her face when she has a go at Kylo Ren.

By contrast, the original trilogy and the prequels are easily taken as male fantasies about both men and women. The tough guys? The guys. When you feel the Force, you get stronger, and you get to choke people, and you can shoot or kill them, preferably with a lightsaber (which looks, well, more than a little phallic — the longer, the better).

But there’s another view. Leia is the leader of the rebellion. She’s a terrific fighter, and she knows what she’s doing. She’s brave, and she’s tough, and she’s good with a gun. By contrast, the men are a bit clueless. She does wear a skimpy costume, and she gets enslaved, kind of, by Jabba the Hutt. But isn’t everything redeemed, because she gets to strangle her captor with the very chain with which he bound her? Isn’t that the real redemption scene in the series?

Thomas Jefferson, Jedi Knight

The series could easily be seen as profoundly political, meant to show how republics turn into empires, and to emphasize the need for rebellion, or at least for maintaining the potential for one. On this view, the need for political freedom is the central message of Star Wars.

The whole tale poses a conflict between an authoritarian Empire and the rebels seeking to restore a Republic. The Empire is more than a little reminiscent of Nazi Germany, and the goal of the Rebellion is to restore peace and justice to the galaxy. Luke Skywalker is initially unwilling to take political action; he hates the Empire, but wants to stay on the farm with his aunt and uncle. (The Empire murders them, which persuades him to act.) “The Force Awakens” continues the basic story with a conflict between the First Order, inspired by the Empire, and the Resistance.

There’s more than a mild echo here of Thomas Jefferson, who thought that turbulence itself is “productive of good. It prevents the degeneracy of government, and nourishes a general attention to the public affairs. I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.”

Rebellion! Is the whole tale based on Jefferson?

Technology

Maybe the series is a cautionary story about the dehumanizing effects of technology.

“A New Hope” begins with droids. In a sense, they are the narrators of the tale, and they have human characteristics; that’s part of their charm. BB-8 plays the same role in “The Force Awakens” as R2-D2 plays in “A New Hope”; the two are like cute pets or loyal younger siblings. But dehumanization through machines, and machine parts, plays a large role throughout the series.

Darth Vader is frightening because he is part person, part machine. Obi-Wan to Luke in “Return of the Jedi”: “When your father clawed his way out of that fiery pool, the change had been burned into him forever — he was Darth Vader, without a trace of Anakin Skywalker. Irredeemably dark. Scarred. Kept alive only by machinery and his own black will.” That is a fact, but it is also a symbol: falling to the Dark Side, he loses much of his humanity — a prescient warning for those who live in an age of machines. (Check your email lately?)

The Dark Side and the Devil’s Party

Say it loud and say it proud: Vader steals the show. He’s the most memorable character in the series. No one else comes close.

The great William Blake, writing about “Paradise Lost,” one of the most religious texts in the English language, pronounced: “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it!” Blake had a point about Milton, who fell for Satan’s energy and charisma.

Was George Lucas also of the Devil’s Party? Not really. In the end, he’s a good guy; he’s Luke. But he did get tempted. Lucas wrote “A New Hope” about Luke, his namesake, but it was the character of Vader who captured his imagination, and so the Sith Lord ended up central to the narrative. The appeal of the Dark Side is what gives the whole tale its necessary tension.

Star Wars can be read in many other ways as well. Maybe it’s about Buddhism, the importance of order, the need for paternal love, freedom of choice, the constant possibility of redemption, the evils of bickering legislatures, or the rise of Donald Trump. You can make a good argument that it’s about every one of those things. As Vader said to Luke, “Search your feelings, you know it to be true.” That’s the secret of its enduring appeal.

(This article is excerpted from “The World According to Star Wars,” from HarperCollins.)

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

No Comment