They Want Their Money Back: Investors Push Back on EU Bailout

published Sep 10, 2018, 5:38:07 AM, by Jasmina Kuzmanovic, Gordana Filipovic and Jana Randow

(Bloomberg) —

In 2013, Slovenia rescued its failing banks by wiping out stock investors and holders of about 600 million euros ($700 million) of debt.

Now some of those investors want their money back.

While their appeals have had limited success so far, a shake-up at the central bank and a ruling from the nation’s Constitutional Court suggest the matter is far from closed. The investors are pushing for a law that would enable them to recoup losses, while putting the tiny Balkan state on a collision course with the European Union and European Central Bank.

“The passing of a law like this would be like opening Pandora’s box,” said Otilia Dhand, senior vice president for central and eastern Europe for Brussels-based Teneo Intelligence. “There would be a risk of national reviews in every country that executed a bail-in.”

Slovenia won permission from European authorities for the 3.2 billion-euro rescue of its largest banks by agreeing that investors—not just taxpayers—would feel the pain. The bailout, coming near the end of the euro area’s sovereign-debt crisis, allowed the Alpine nation of 2 million people to avoid a Greece-style international rescue program.

Kristjan Verbic, who leads the Pan-Slovenian Shareholders Association and represents investors hit by losses, has been a public face of the campaign seeking reimbursement. He cites a ruling by the Constitutional Court that found that while the bailout wasn’t illegal, existing law didn’t go far enough in protecting investors. He also points to rescues in Spain, Portugal and Italy, where retail investors were in some cases deemed entitled to reimbursement.

“Slovenia is unique in its complete lack of even a discussion of compensation,” Verbic said in an emailed response to questions, citing a June study from the European Parliament.

Bostjan Jazbec, who led Slovenia’s central bank during the bailout and stepped down in May, has borne the brunt of the criticism. Questions over the handling of the rescue led to a police investigation, including a 2016 raid on his office that both the Bank of Slovenia and the ECB condemned as an infringement of central bank independence. Slovenian police declined to comment on the investigation, citing privacy laws.

Jazbec defended the central bank’s actions and the resulting decision to impose losses on junior bond holders. A stress test conducted by the ECB the following year still found minor capital shortfalls at two institutions, which shows that he and his colleagues weren’t too strict, he said.

How the dispute progresses will be up to the country’s next government. After inconclusive April elections, a political outsider—comedian-turned-mayor Marjan Sarec—has been elected prime minister and is cobbling together a minority administration. His cabinet is set to face a confirmation vote in parliament on Thursday.

One of its first tasks will be the choice of a replacement for Jazbec. The government must also start the sale of Slovenia’s largest bank, Nova Ljubljanska Banka, after its predecessor missed the deadline imposed as part of the financial rescue.

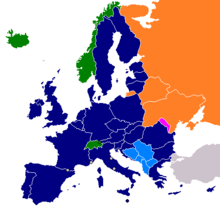

Nestled between Italy, Austria, Hungary and Croatia, Slovenia has long struggled to unravel the links between politics and the economy. While it was the first former Yugoslav republic to join the EU, and later adopt the euro, the nation has dragged its feet on reforms, including the sale of state companies.

Years of mismanagement and political influence plagued the banks. In 2013, Alenka Bratusek, then prime minister, turned to taxpayers to bail them out after rising loan defaults brought them to the brink of collapse. Jazbec’s central bank calculated the capital shortfalls in a report that was audited by Deloitte and approved by the European Commission.

“Everything that we as a government did in 2013 during the bank bailout was appropriate,” Bratusek said in a phone interview.

Now a shakeup at the central bank could work in favor of those hit by losses. Jazbec’s acting replacement as governor, Primoz Dolenc, was formerly director of the treasury department and head of risk at Abanka DD. a lender whose written-off debt is a focus of investors’ efforts to recoup losses. His No. 2, Vice Governor Irena Vodopivec, served on Abanka’s supervisory board.

Since Jazbec’s exit, the office of the governor was dissolved and the heads of business development and supervision, along with his spokeswoman and legal counsel, are being let go, said people familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified discussing private matters.

“The ultimate goal is that investors get their money back, and the central bank can pretend not to know the details about the bail-in,” Jazbec, who moved to a job at the EU’s Single Resolution Board, said in an interview. Such an outcome “would set a precedent to challenge any supervisory decision ex-post,” he said.

The Bank of Slovenia said it couldn’t comment on the matter “due to the regulatory requirements of protecting employees and their personal data.”

“Having said that, Banka Slovenije is in the process of reevaluating various measures that would increase its efficacy and institutional efficiency,” it said in an emailed response to questions. “We have also reached consensual agreements with all staff that has already been affected.”

Slovenia’s judiciary has also weighed in. In October 2016, the Constitutional Court gave legislators six months to change the law on banks to better protect investors.

That deadline came and went, and a bill proposed by the finance ministry failed to progress through parliament last November. In an e-mail, the ministry said it hopes “further activities for the adoption of the law will take place immediately after the formation of the new government.”

An ECB assessment of the draft bill last October said it may conflict with EU rules, including a law putting assessments by the European Central Bank outside the jurisdiction of national courts.

The Slovenian central bank said it had no information as to whether the government would propose the same draft law, but that it had comments on the bill “and we expect that we will be able to discuss them with the relevant authorities.” It said the draft doesn’t give investors an “automatic right” to compensation.

The draft legislation includes some measures that could contradict the norms of central bank independence and that may wrongly benefit speculative investors, said Igor Masten, a professor of economics at the University of Ljubljana.

“The integrity of the entire eurosystem is at stake here,” Panicos Demetriades, a former Governing Council member who published a book about his own experience as head of the Cypriot central bank, tweeted in response to this story. “It’s not just Slovenia.”

Panicos Demetriades@pdemetriades @Skolimowski @jaskuzmanovic @gfbelgradenews @jrandow Very bad idea. Executives whose banks have failed aren’t fit a… twitter.com/i/web/status/1…

To contact the authors of this story: Jasmina Kuzmanovic in Zagreb at jkuzmanovic@bloomberg.net Gordana Filipovic in Belgrade at gfilipovic@bloomberg.net Jana Randow in Frankfurt at jrandow@bloomberg.net

COPYRIGHT

© 2018 Bloomberg L.P

No Comment