Gregg Allman’s Passing and the Bizarre World of Downtown Nashville : A Well Thought Out Scream by James Riordan

Gregg Allman died at his home in Savannah, Georgia, on May 27, 2017, due to complications from liver cancer. I remember the first time I saw him was at the Pancake Man Restaurant located in the downtown Nashville Holiday Inn on Friday October 30, 1970. The Allman Brothers had just opened for Jesse Colin Young and the Youngbloods at Vanderbilt University. They had just released their second album and were developing a following, but it wouldn’t be until the following July that Live at the Fillmore East would catapult them into major rock stardom. Nashville is home to some of the nicest and most talented people in the world, but Nashville in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s was also home to some strange folk. Of course, a lot of these people only came out at night and that’s why one of the most bizarre place I have ever regularly visited was the Pancake Man.

Gregg Allman in recent years

Let me break down the basic after midnight clientele of the Pancake Man. First you had your Grand Ole Opry performers. Now, this was back when the Opry was in the Rhyman Auditorium in downtown Nashville and not in its own theme park. Occasionally, a legitimate country music star dined at the Pancake Man but not that often. But many second tier acts and their bands and backup singers always ate there. Then you usually had a representative or two of the legions of honky tonk singers that performed all over Nashville, but especially in the downtown area. Now, I don’t know how well you know your basic Honky Tonker but think of a bunch of David Allen Coes without the fame and the money and you’ll get the idea.

Another key ingredient of the Pancake Man crowd was the strippers and hookers. There were like seven thousand strip bars in downtown Nashville then and each one had fifteen girls working there. Okay, that’s an exaggeration. Let’s just say there were always a few there. Since Nashville was a major recording center then as well as now, you had all kinds of session musicians hanging around, some of whom were legends themselves.

Downtown Nashville was also host to big wrestling shows and there were always a tag team or two wolfing pancakes there at two in the morning. I don’t know how many professional wrestlers you know but, in public, they are pretty much like they are on stage except they don’t body slam you on your face and put you into a figure-4 leg lock, unless you make them mad. But they’re really loud.

Then you had songwriters, armies of them – three James Taylors, two Joan Baezes, four Carole Kings, two Carly Simons and three sets of Simon and Garfunkles. Some of these were hippies as well and that was the slot in which I and my co-habitators fell. I readily admit that myself and the three to five other songwriters who lived in that wild house on Central Avenue back then were pretty strange ourselves – which is why we belonged with the late night Nashville crowd.

Then you had songwriters, armies of them – three James Taylors, two Joan Baezes, four Carole Kings, two Carly Simons and three sets of Simon and Garfunkles. Some of these were hippies as well and that was the slot in which I and my co-habitators fell. I readily admit that myself and the three to five other songwriters who lived in that wild house on Central Avenue back then were pretty strange ourselves – which is why we belonged with the late night Nashville crowd.

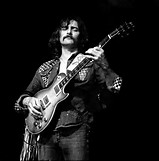

Gregg when he was young

So this one Saturday night we’re eating eggs and the Pancake Man is in its full glory, overflowing with the previously mentioned folk. In comes the Allman Brothers, fresh from their concert at Vanderbilt University. This is the original band before they started dropping like flies caught in the heyday of the ‘60s rock myth. Duane Allman was still alive. Eric Clapton had already said he was an amazing guitar player and he’d already been in Rolling Stone. Duane was tall, over six foot I think, but a little shorter than Gregg. Both of them had long strait hair, down past their shoulders. Gregg’s was pure blond and Duane’s was red. Rock gods. And Dickie Betts stood next to them, already being recognized himself as a great guitar player. I believe that Butch Trucks, Jaimo and Berry Oakley were also there, but I can’t be positive (like everything else about the human body, the memory does its dance).

I remember them scanning the room as they waited for a table and watching the look in their eyes as they took in the downtown Nashville menagerie. After a few minutes, Dickie Betts looked over at us and, recognizeing kindred spirits(longhairs), came over to our table. He said, “Hi, I’m Dickie Betts of the Alman Brothers. We just got done with our gig at Vanderbilt and…” Then he paused as he watched the Alaskens (their Wrestling stage name), one of our tag team patrons, go into one of their fake tantrums with another wrestler whose name I didn’t know but who we called the “Giant Craig” because he looked like a larger version of a good friend of ours. When the professional wrestler’s pseudo tantrum was done, Betts looked at me and said, “What the heck’s the deal with this place?” I did my best to explain late-night Nashville to him and he marveled along with us that such a place could survive very long. A few years later when I was writing my syndicated column on pop music, I got invited to the Capricorn Records picnic and hooked up with Dickie again. By then half his band was dead (Duane and Berry Oakley both died in motorcycle accidents), but we reminisced a bit.

Nashville by day wasn’t much more normal, especially to some Illinois boys like us. One time Mike Leppert and I had written a tune we thought was perfect for Bobby Goldsboro, the reigning country king of smaltz ballads who’d had huge hits with “Honey”, “Little Green Apples” and “Watching Scottie Grow”. I wrote these lyrics called “Another Busy Day” and it was all about this guy who adored his wife and could never afford to take her to Paris and give her all the things she deserved. We took it to Kenny O., Bobby’s song guy, who ran his music publishing companies. Well, like most Nashville music execs, Kenny was a real nice guy and made time to listen to our latest batch of songs. In fact, people are so nice in Nashville that it takes six months for you to figure out they’re just giving you the run around. In L.A. you learn that in about an hour. In New York, about ten minutes.

Nashville by day wasn’t much more normal, especially to some Illinois boys like us. One time Mike Leppert and I had written a tune we thought was perfect for Bobby Goldsboro, the reigning country king of smaltz ballads who’d had huge hits with “Honey”, “Little Green Apples” and “Watching Scottie Grow”. I wrote these lyrics called “Another Busy Day” and it was all about this guy who adored his wife and could never afford to take her to Paris and give her all the things she deserved. We took it to Kenny O., Bobby’s song guy, who ran his music publishing companies. Well, like most Nashville music execs, Kenny was a real nice guy and made time to listen to our latest batch of songs. In fact, people are so nice in Nashville that it takes six months for you to figure out they’re just giving you the run around. In L.A. you learn that in about an hour. In New York, about ten minutes.

Duane Allman

Berry Oakley

Anyway Kenny listened to the tape and didn’t find anything to his liking. I made a point of asking him about “Another Busy Day” because I thought it was Bobby’s type of song, but he passed. So then, Mike and I went across the street (actually across the alley) that ran between 16th and 17th Avenues, an area called Music Row in those days because of all the music compa-nies located there. We took the song over to a guy named Larry who worked for Don Tweedy, Elvis Presley’s arranger at the time. Larry put the tape on and as soon as he got to “Another Busy Day” he stopped the machine and said. “This song is perfect for Goldsboro.” I said that I had thought so too but Kenny passed on it.

Larry nodded. “Let’s take it over to Kenny right now.”

“I was just there,” I replied. “He didn’t like it.”

Larry nodded again. “Let go over there and play it for him.”

I looked at Mike and Mike shrugged. “No, we were just there, not fifteen minutes ago and he passed on the song.”

Larry nodded. “Alright, let’s go then.”

Who am I to question the marvelous minds of Nash-ville music? I got up and Mike and I followed Larry right back to Kenny’s office. When we entered, Larry said, “Hey Kenny, we got a song we think would be great for Bobby.”

I said, “Hi Kenny, you remember us. We were here like twenty minutes ago.”

Kenny said, “Hello boys. Yeah let’s hear it!”

Then he put the same tape back on the same machine where he had listened to the song before.

Larry said. “It’s the third song. It’s called “Another Busy Day”.

Kenny nodded and fast forwarded the tape to the song.

Bobby Goldsboro

I said, “Remember, it was the one I pointed out to you.”

Kenny said, “Alright, let’s take a listen.”

I looked at Mike. Mike shrugged. I shut up.

Kenny played the song. After about a minute he said, “Yeah, this is Bobby’s kind of song alright.”

Larry agreed. “And Glenn too. We’ll get a lot of cuts on this.”

“Cuts” is music publisher slang for recordings and by Glenn I assumed they meant Glenn Campbell, another big star of the time.

“Maybe even Johnny or Waylon,” Kenny added and Larry nodded.

When the song was over Larry said, “Alright I found the song so I get half of the publishing and you and Bobby can have the other half.”

“That’s fair,” Kenny said. “But you got to do the demo.”

“Okay,” Larry said. “I might just record it on the album I’m working on and we can use that as a demo to pitch it. I’ll draw up the song-writing contracts with the boys here.”

Then he turned to me and said, “Congratulations, boys. You got a hit song in the works.”

Now, as things tend to go, Larry’s album got bogged down so we never got our demo and then he left the company so our song was stuck with someone who didn’t care about it. But that day, as I sat in Kenny’s office, I couldn’t help myself from looking the gift horse in the mouth. After all the talking was done, I said. “You know Kenny, when I played you that song like, oh about a half hour ago, you passed on it. How come?”

He looked at me for a long moment and then he said, “I just couldn’t hear it then.”

I use this story in my book The Platinum Rainbow because it illustrates what I call “The Well Respected Source Rule” which means that, since the arts are so subjective, you always have more power when someone successful brings in your project. That why agents work so well. Kenny was telling the truth. He couldn’t hear it when the song was coming from two kids that were living in a ’65 Chevy. But when Larry, a respected songwriter/publisher, played it for him, he heard it loud and clear.

As you might have guessed, things didn’t work out. Larry published the song, but then he left Don Tweedy Music, before he recorded it. Once Larry was gone, Kenny had no tie to the song and it just faded away. Kind of like the Allman Brothers but there was so much passion and fire in that original band it took a long, long time to die.

___

No Comment