Americans Are Dying Faster. Millennials, Too

(Bloomberg) —Death awaits all of us, but how patiently? To unlock the mystery of when we’re going to die, start with an actuary.

Specializing in the study of risk and uncertainty, members of this 200-year-old profession pore over the data of death to estimate the length of life. Putting aside the spiritual, that’s crucial information for insurance companies and pension plans, and it’s also helpful for planning retirement, since we need our money to last as long we do.

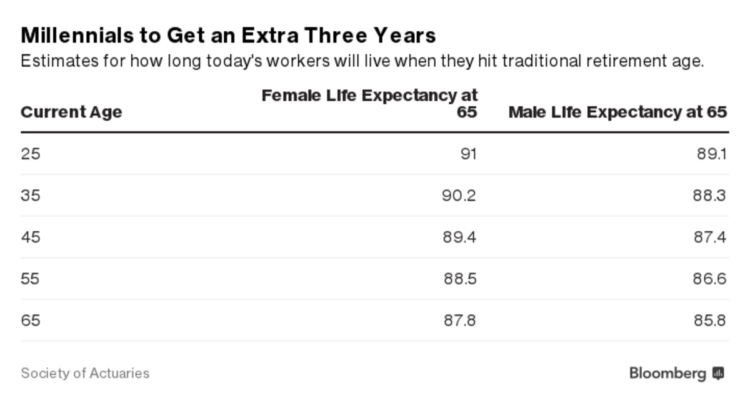

The latest, best guesses for U.S. lifespans come from a study (PDF) released this month by the Society of Actuaries: The average 65-year-old American man should die a few months short of his 86th birthday, while the average 65-year-old woman gets an additional two years, barely missing age 88.

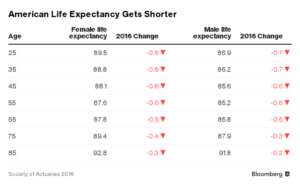

This new data turns out to be a disappointment. Over the past several years, the health of Americans has deteriorated—particularly that of middle-aged non-Hispanic whites. Among the culprits are drug overdoses, suicide, alcohol poisoning, and liver disease, according to a Princeton University study issued in December.

Partly as a result, the life expectancy for 65-year-olds is now six months shorter than in last year’s actuarial study. Longevity for younger Americans was also affected: A 25-year-old woman last year had a 50/50 chance of reaching age 90. This year, she is projected to fall about six months short. (The average 25-year-old man is expected to live to 86 years and 11 months, down from 87 years and 8 months in last year’s estimates.) Baby boomers, Generation X, and yes, millennials, are all doing worse.

Americans increasingly need an accurate sense of how long they’ll be alive. Employer shifts from traditional pensions—which sent a regular check for life—to individual 401(k) accounts mean workers must figure out retirement on their own. When you die becomes a crucial variable, helping to determine how much you need to save and how much you can afford to spend: Die at 95 and your retirement could be twice as expensive than if you die at 80. Information on mortality also helps set the price of annuities, insurance contracts that can pay buyers a set amount of money for the rest of their lives.

Some of the most commonly cited estimates of longevity are misleading for anyone putting together a retirement plan. For example, the life expectancy for Americans at birth is 76 for men and 81 for women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But if you’ve already survived to middle age, you have a good chance of living much longer. The Society of Actuaries’ website offers a longevity calculator that takes both your age and health into account.

Estimating longevity is as much an art as a science. The simplest way to calculate life expectancy is to look simply at how many people are dying at every age. If you want to know a 25-year-old’s chances of hitting age 100, you just calculate her statistical chances of getting through the next 75 birthdays unscathed. Looking at current data, what are her chances of dying at 25, 26, 27, 28, and so on?

The problem with this simple calculation is that it assumes life expectancy won’t improve over the next 75 years. Today’s 25-year-olds could be kept alive by safety technologies and medical treatments that don’t exist yet. At least, we hope.

So, baked in to the Society of Actuaries’ calculations is an assumption that longevity will keep improving. It looks at recent data to estimate near-term improvements.

The latest numbers, however, aren’t pretty: From 2000 to 2009, American death rates improved at 1.93 percent for men and 1.46 percent for women annually. From 2010 to 2014, that plunged to 0.6 percent for men and 0.42 percent.

This is bad news for almost everyone but pension fund managers. Still, it’s not time to panic yet.

“Year-over-year changes in mortality are very volatile,” said Dale Hall, managing director of research at the Society of Actuaries. Over time, death rates jump up and down a lot: All it takes is a bad flu season or the onset of a novel disease to make for a bad year, while new drug treatments for heart disease can produce several excellent years.

Actuaries assume that eventually, longevity improvements will get back on their long-term track. Still, the bottom line is that longevity’s rise has slowed way down. When they reach the traditional retirement age of 65, the average millennial should get just a few more years than the average baby boomer.

If Americans’ health continues to decline, these estimates could prove optimistic. Then again, the actuaries might be not be able to see huge improvements around the bend. The long-term historical record is encouraging: For two centuries, researchers have found (PDF) life expectancy in the world’s healthiest countries to have risen at a more-or-less steady rate of an additional three months for every year that passes, or 2.5 years a decade. In the 1840s, Swedish women were living to an average age of 45. Today, Japanese women have a life expectancy of 87. If the U.S. somehow got back on this track, today’s 25-year-olds should have an extra decade of life by the time they’re at retirement age.

That future may have already arrived for some Americans—the very wealthy. According to research earlier this year in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a 40-year-old man in the top 1 percent can expect to live 14 years longer than his counterpart in the bottom 1 percent. Education may also make a difference: A college-educated 25-year-old can expect to live a decade longer than a high school dropout of the same age, according to the Population Reference Bureau.

If you’re trying to figure out how long you’re likely to live, estimates of “average” life expectancy may not be that helpful. That’s getting worse in an age of rising inequality. Great medical care and good fortune may add decades to the lives of the wealthy and educated, while much of the rest of America is left behind.

Watch Next: Confused About What to Eat? You’re Not Alone.

To contact the author of this story: Ben Steverman in New York at bsteverman@bloomberg.net To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rovella at drovella@bloomberg.net

copyright

© 2016 Bloomberg L.P

No Comment