The Five Major Causes of Mass Murder in America – PART THREE : The Culture of Fame and the Pressure of Consumerism : A Well Thought Out Scream by James Riordan

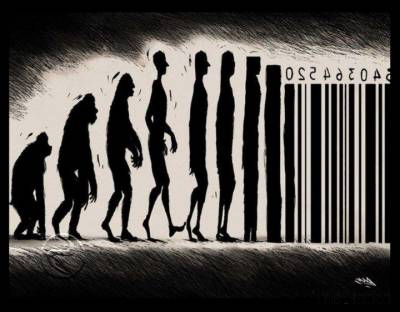

After much detailed research for a book I am writing entitled Ready to Pop : The Rise of Mass Murder in America, I have come to the conclusion that there are five factors in America today which have combined into a perfect storm to fuel mass murder including school shootings. A single factor applies to a greater or lesser degree depending upon the age of the shooter. These factors are : Access to Guns, Familiarity with Violence, The Pressure of Consumerism, The Lack of Proper Mental Health Treatment and The Culture of Fame. Part One of this series looked at Access to Guns and Familiarity with Violence. Last week we examined The Lack of Proper Mental Health Care. This week we will look at Part Three : The Culture of Fame and The Pressure of Consumerism.

The Culture of Fame

The desire for fame is at its highest level. A recent survey of high school students reveals that over a third of them said their goal in life was to become famous. For years, fame has been the unstated “bonus” for young people claiming they desired careers as actors, musicians and sports figures, but in recent years people are acknowledging that it is the real goal as if they don’t really care what kind of career they have as long as people know their name. Not only that but a ridiculous 51 percent of 18 to 25-year-olds think they will be famous one day. But it starts even younger than that. When parents asked their children as young as 5 what they wanted to be when they grew up, 19 percent said they wanted to be famous. But maybe this new development shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, considering that the TV targeted at children in the last decade, like American Idol and Hannah Montana, has placed more value on fame than ever before.

The problem is that being famous is replacing traditional goals. When a poll of 16-year-olds finds that 54 percent of them want to be famous, but only one percent want to work in an office and four percent want to become teachers, you are setting a whole generation up for a lifetime of feeling like a failure. Working in a sea of cubicles is soul-destroying enough without your broken dreams hanging over you the whole time.

Virtually everyone alive in America today wants to be famous. Since the rise of television back in the early 1950s, mort people in America have wanted to be famous, and now that most of the people who lived before that time have passed away we are left with attaining fame as part of the American Dream. People magazine was founded in 1974 to “focus entirely on the active personalities of our time.” Now people pages are in news magazines, television shows like Entertainment Tonight and its imitators, even the New York Times Magazine.

Virtually everyone alive in America today wants to be famous. Since the rise of television back in the early 1950s, mort people in America have wanted to be famous, and now that most of the people who lived before that time have passed away we are left with attaining fame as part of the American Dream. People magazine was founded in 1974 to “focus entirely on the active personalities of our time.” Now people pages are in news magazines, television shows like Entertainment Tonight and its imitators, even the New York Times Magazine.

In recent years the culture of fame has grown even more because people have realized that you don’t really have to be exceptional at something to attain fame. In the past, natural born talent, learned skills, and a hard work ethic seemed to be necessary with the exception of the few who caught a lucky break. In fact, the truth was you had to be talented, have developed great skill in your field and worked very hard to make even a lucky break pay off. But today, with the likes of Paris Hilton, the Kardashians and Honey Boo Boo, people know there is no prerequisite of talent and hard work to be famous. We live in a culture where popular media often accords fame to people who have accomplished little or nothing of any great significance. The reality TV world is obsessed with entertainment above all means that young people have come to believe that the path to happiness is having your fifteen minutes of glory where everyone knows your name.

America is infatuated with the celebrity as if these people were superhumans, powered by glamour, glitz, and lots of cash. They have been given an almighty status, seen as an elite, separate species of their own— which has become a fixture in our society. We can’t get enough of them! We want to know not only what they wore to their movie premiere, but also what they wore taking out the trash that same morning. We want to know about their weight issues, what they look like without make-up, the details of their latest breakup, their holiday recipes, and how we can look like them. Welcome to America: land of the free, home of the famous.

In truth, the narcissism of the 21st century, is neither a sudden nor an entirely new phenomenon. “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about,” Oscar Wilde’s Lord Henry remarked in 1890’s “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” “and that is not being talked about.” The world Wilde anticipated can be explained by a few key texts that illuminate how we find ourselves with a president of the United States who used to call up New York tabloid writers posing as Trump spokesman “John Miller” or “John Barron” to talk about … himself. As Daniel J. Boorstin wrote in his landmark 1961 book THE IMAGE: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America: “Fame, which had once been based largely on achievement or on high birth, was becoming more a matter of “a person who is known for his well-knownness.” Aside from his definition of fame — a similar point to Andy Warhol’s better-known remark that in the future everybody would be famous for 15 minutes — Boorstin’s key contribution was the notion of modern life as a series of “pseudo-events.” A pseudo-event, Boorstin wrote, was, first, “not spontaneous, but comes about because someone has planned, planted or incited it. Typically, it is not a train wreck or an earthquake, but an interview” — or a tweet. Second, it is “planted primarily … for the immediate purpose of being reported or reproduced. Therefore, its occurrence is arranged for the convenience of the reporting or reproducing media.”

In regards to Warhol’s quote about a future where everyone would be “famous for fifteen minutes,” it has turned out that through Facebook and the like, everyone is “famous to fifteen people.”

Public life in particular is thus not organic but manufactured and manipulated for the maximum advantage of those doing the manufacturing and the manipulating. Joe McCarthy was, in Boorstin’s words, “a natural genius at creating reportable happenings that had an interestingly ambiguous relation to underlying reality.” As Richard Rovere of The New Yorker wrote in his book about the senator’s rise to power, McCarthy “invented the morning press conference called for the purpose of announcing an afternoon press conference. The reporters would come in … and McCarthy would say that he just wanted to give them the word that he expected to be ready with a shattering announcement later in the day, for use in the papers the following morning. This would gain him a headline in the afternoon papers: ‘New McCarthy Revelations Awaited in Capital.’ Afternoon would come, and if McCarthy had something, he would give it out, but often enough he had nothing, and this was a matter of slight concern. He would simply say that he wasn’t quite ready, that he was having difficulty in getting some of the ‘documents’ he needed or that a ‘witness’ was proving elusive. Morning headlines: ‘Delay Seen in New McCarthy Case — Mystery Witness Being Sought.’” And so McCarthy, simply by asserting things that may or may not have had any connection to reality, dominated the life of the age.

Paris Hilton

By 1978, when Christopher Lasch wrote The Culture of Narcissism, the indignant cultural critic could define an entire age in terms of a personality disorder where all of America was fixed on itself with a kind of “transcendental self-attention.” Lasch noted that the narcissist identifies with individuals of grandeur, because he believes he is like them—and he labeled our entire culture narcissistic: thus our increasing need for celebrities. More and more we live in what Boorstin called the “illusory” world of created characters. Whatever harm this may do to us—critics point out that mass-marketed images fit only a few people and stigmatize many, as opposed to homemade stories in which we each learn about ourselves and our own possibili-ties—it does serve an important purpose. The culture of celebrity, biographer Gabler emphasizes, has been able to “bind an increasingly diverse, mobile, and atomized nation until it became, in many respects, America’s dominant ethos.”

Instead of gossiping over the back fence about our neighbor, we now gossip with strangers about other strangers (celebrities) all over the world. “We treat celebrities as characters in an ongoing, shared soap opera of America that we all watch,” says Mark Harris, senior editor at Entertainment Weekly. “Their failures, successes, sudden deaths, twist endings, windfalls and comebacks…we get a new episode daily courtesy of the media boom.”

Yet for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, and so a certain cynicism has set in among us all, and a rabid fascination not only with the false beauty of the glorified, sterilized celebrity, but also with the dark and seamy underside. “We live in a media culture that encourages people to think two different things,” notes Harris. “One is that celebrities live lives we can’t possibly imagine, and they are worthy of our slavish devotion, attention, and respect.

“The other is that celebrities are just like us, they’re people with problems, and they drink too much or hit their wives or have bad relationships. Of course those are opposing beliefs, that they are just like us and nothing like us, but the illusion that we can get to know these people gives fuel to a lot of subsidiary enterprises in the media.”

Kim Kardashian

Harris believes that the balance has shifted in favor of the dark morality tale: “What we really look to celebrities for today is the reassuring moral tale. ‘Oh look, he just got $10 million for his new movie—but his wife is leaving him.’ ‘She’s so famous, everybody loves her; too bad she drinks.’ There’s a booming industry now in proving celebrities can be just as miserable as the rest of us.” At a certain point the debunking has to take place, whether or not there’s something to debunk, notes Kramer. Sensing that these people are manufactured, we seem to have developed an appetite for both their inflated and deflated selves. We want to both elevate and destroy our celebrities.

They also add excitement to our lives. Peter Kramer, a psychiatrist and doctor who wrote Listening to Prozac, said, “We have strong feelings about all these celebrities and we don’t have enough intimate passion in our lives. There is the whole sequence of building up, deflating, and rehabilitating heroes. It seems to go on endlessly and repeatedly. It’s risk free for most of us.”

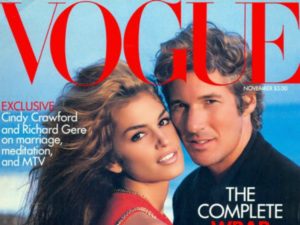

The very technology that has brought heroes, albeit manufactured ones, into every home has also brought the stark, vivid images of their failures and vulnerabilities and mortality into our bedrooms and living rooms, on television and in newspapers. Today we shuttle routinely between Ivory-soap versions of celebrities—their perfect marriages, perfect children, and perfect careers—and genuine slander. Cindy Crawford and Richard Gere become the golden couple when they are first married, only a few years later having to take out full-page newspaper ads to protest that they are not homosexual and that their marriage is real. Soon after, they divorce.

Celebrities have been demoted from gods of the natural world to agents of the flow of information. Courtney Love, wife of deceased grunge star Kurt Cobain of Nirvana fame, bares her soul on late-night E-mail forums, and anybody in America can read or reprint her thoughts and confessions. A photo of Terri Hatcher is down-loaded 400,000 times in a day onto computers around the world—and that fact is written up in Time magazine, along with the original photo and Hatcher’s opinion about her moment of popularity.

Celebrities have been demoted from gods of the natural world to agents of the flow of information. Courtney Love, wife of deceased grunge star Kurt Cobain of Nirvana fame, bares her soul on late-night E-mail forums, and anybody in America can read or reprint her thoughts and confessions. A photo of Terri Hatcher is down-loaded 400,000 times in a day onto computers around the world—and that fact is written up in Time magazine, along with the original photo and Hatcher’s opinion about her moment of popularity.

“Fame,” notes Leo Braudy, Ph.D., professor of English at the University of Southern California and author of The Frenzy of Renown, “has become so immediate that it has lost its posterity. We have a growing sense of impermanence. With the media you have the sense that our entire definition of true fame is visibility. We eat people up a lot faster:’ he contends.

Where President Roosevelt was never photographed below the waist, to protect the public from the image of a disabled leader, President Clinton is asked to describe his underwear, and the presidency is devalued along with us. Technology allows us to tap the talk of lovesick, adulterous princesses and princes on cellular phones, and air those utterly damning conversations over TV and radio. It makes information so accessible that the wish for kings is transformed into the wish to know.

According to Braudy, Alexander the Great was the first famous person in a modern sense, who wanted to be recorded for the ages in stone and in paint. “Not only did he want to be unique, but he wanted to tell everybody about it, and he had an apparatus for telling everybody about it. He had techniques for doing famous things. He had historians, painters, sculptors, gem carvers on his battles.”

If our gods are no longer permanent, if our heroes are murderers, if our political leaders are exposed as compulsive adulterers or tax evaders, then we can no longer fill ourselves up on them in quite the same way. Instead, we drown in information, and use it to allay the anxiety of a godless and ever-shifting culture. Our endless lust for stories derives in part from the pure pleasure of it—but also to distract us from our deeper anxieties.

“There is an amazing desire on the part of the consumer to have an edge, to know a little bit more than the next guy,” comments Mark Harris, “and to know it a little bit sooner, a little more fully. One of the most popular things we do in the magazine is to print the weekend’s box-office grosses. People love that. They can figure out who is winning and who is losing.”

Today, information comes at us with incredible speed, in innumerable changing faces and stories, on Court TV, on CNN in 24-hour play. We have far too much information about celebrities these days—their love affairs, their private conversations on cellular phones, the color of their underwear, how many nose jobs they’ve had, how many intestinal polyps our presidents have had removed. But the surfeit of information strips the famous of the sacred and heroic—therefore our culture and our own lives—as heroes reflect what we believe is best in ourselves.

When it comes to fame, we have created a monster that continues to grow even when it only feeds on itself. The internet constantly provides updates on the lives of celebrities. Every romantic gesture, angry face and muttered asides becomes a headline. News sources produce a story involving either an overpaid actress or an overhyped reality star nearly every week. You would think that the public would get fed up with the constant barrage of tabloids, talk shows, and trending stories concerning celebrities like the Kardashian clan, but they don’t. It seems that the more people hear about someone, the more they want to hear.

Celebrity in America has always provided an easy an outlet for our imagination and that is something people in today’s world need. In the same way the gods of ancient Greece and Rome once were, celebrities are our myth bearers, carrying such powerful forces as love, hate, good, evil, lust, and forgiveness. “The wish for kings is an old and familiar wish, as well-known in medieval Europe as in ancient Mesopotamia,” wrote Lewis Lapham in his book The Wish For Kings. “The ancient Greeks assigned trace elements of the divine to trees and winds and stones. A river god sulks, and the child drowns; a sky god smiles, and the corn ripens. The modern Americans assign similar powers not only to whales and spotted owls but also to individuals blessed with the aura of celebrity.”

Twenty percent of surveyed high school students said their goal in life was to make a difference in the world before they died. While such a goal may seem too ambitious to many, it does not hinge on having a world-wide effect, but rather on making a positive rather than negative contribution and that is far more attainable than the goal of fame. We don’t have much control over whether we become famous or not, but we do have a great deal of control over whether or not we give something to the world while we are here. The problem with the fame goal is the only real way to guarantee it is to do something negative. The brave man who dove into a river to save a drowning girl will be remembered, but only for a short time, while the Columbine shooters will be burned into our memory forever.

The pursuit of fame has dominated technological devices and media, resulting in our youth fixating on obtaining it. In today’s society, there are several degrees of fame. A person can be famous on Facebook, Instagram, You Tube or Snapchat. They can be famous in their school, in their neighborhood, in their town or famous amongst people who like a certain person or thing such as being famous among surfers, ski boarders, baseball card collectors or Jim Morrison fans. When it comes to social media, the higher number of friends or subscribers, the higher likelihood for fame and being Internet famous can quickly transform into real-world famous. Many a YouTube star has successfully turned their Internet popularity into mainstream-media and appeared on popular magazine covers or television shows.

Never underestimate the power of an image. Images transmute celebrities into com-modities to be sold for a price. In Claims to Fame: Celebrity in Contemporary America (University of California Press), Yale’s Joshua Gamson quotes 1930s screen star Myrna Loy. “I daren’t take any chances with Myrna Loy, for she isn’t my property…I couldn’t even go to the corner drugstore without looking ‘right,’ you see. Not because of personal vanity, but because the studio has spent millions of dollars on the personality known as Myrna Loy.”

Celebrity produces both adulation and disgust, worship and resentment. If you ask even the most dedicated of Kardashian fans why they watch the show, they will make some reference to the program being funny because the family is so screwed up. Even their fans don’t want to admit their adulation, but the truth is they want to be the Kardashians. Such idols represent both what we strive to be and what we find most distasteful about society.

Also, we view them from a safe distance, far enough away that we can point out their flaws, especially things like weight-gain and bad bathing suits. Even though we know we ourselves could never stand such endless scrutiny and pressure. Still we persist in our endless critiquing, knowing that their fame entitles us to put them down. This allows us to embrace that fine line between adulation and disgust— hating them for their perceived perfection, endless attention, money, and fabulous cars while all the while wishing we were just like them.

Peter Kramer, a psychiatrist and doctor is the author of Listening to Prozac, a book that garnered him his own measure of fame. “There is so much specialized media that the amount of material they require is extraordinary,” he noted. “I was amazed at the number of outlets on my book tour. Any small city has cable stations, drive-time morning shows, women’s shows—you name it. The sheer amount of material needed to run the media we consume is enormous, so you have to create lots of characters.”

The selling of persona has permeated even traditionally pure fields. The publication of literary novels has become a celebrity-making event. In hallowed academe, professors are now marketed as personalities. “The genteel tradition of the gentleman scholar has given way to the academic hustler; the self-promoter and entrepreneur whose name is everywhere,” explains John Rodden, an adjunct professor at the University of Texas and author of The Politics of Literary Reputation.

Thirty years ago in his landmark book, The Image, historian Daniel Boorstin defined modern fame in terms that have resonated ever since. “The hero was distinguished by his achievement, the celebrity by his image. The celebrity is a person well known for his well-knownness. We risk being the first people in history to have been able to make their illusions so vivid, so persuasive, so realistic that we can live in them.”

If there is one aggregate truth about America that celebrities also tell us, it is, Braudy points out, “the basic myth of an individual and country that is self-created.” Every time an individual creates him or herself out of whole cloth—when a sexually abused black girl becomes an Oprah Winfrey, the single most powerful woman in America—we are reconfirmed in our essential notion of who we, as Americans, are.

The images of the celebrities of old were carved in rock and painstakingly painted of the walls of cathedrals whereas now they enshrined on celluloid or video tape into widely viewed broadcasts and endless reruns and are mass printed onto products marketed, sold, and disseminated with a speed inconceivable to the heroes of old, and then just as quickly cast aside.

“We’re in the Kleenex phase of fame,” noted Braudy. “We see so much of people, and in all branches of the media. We blow our nose on every new star that happens to come along and then dispose of them.”

Technology has made fame more instantaneous—and our fascination with it has become more fickle. At one time the famous were accorded an almost godlike status that seemed permanent, even historical. Look at Alexander and Julius Caesar, but also Babe Ruth and Al Jolson. The celebrity of today is part of the information age. In our digital world information is instantly available and massive in quantity, but as perishable as the click of the remote. The celebrities of our time personalize this information by putting a human face on it, but they and we are somehow lessened by the process. “There has been a tremendous increase not only in coverage of celebrities but in the number of carries themselves,” observes Dana Kennedy, senior writer at Entertainment Weekly. “Thirty years ago the only real celebrities were in the movies. Now they’re everywhere”—radio hosts, lawyers, murderers, teenagers. As a result, “celebrities are just less interesting. Take Ingrid Bergman. She was beautiful, talented, a movie star, and then she went and brought a big scandal upon herself, and then triumphed with an Oscar. She was a perfect celebrity. These days we have people like Tony Danza. Who cares?”

Upon reading that quote, younger readers will no doubt ask “Who is Tony Danza?” That is the point. People are already asking, “Who is Paris Hilton?” Someday not so far away, people will ask “Who is Kim Kardashian?”

The real problem with trying to obtain fame is that fame is addictive, but not satisfying. Fame doesn’t mean very much once you have it, but most of the people who obtain it equate that dissatisfaction with not having enough of it. The truth is no amount of fame will ever be enough. There will always be someone more beautiful, more successful, or more famous than you. If your measure of success comes from outside you will never be happy. All the spiritual teachers throughout history have taught that the secret to happiness is to give, to be of service while we are here. The happiest people are almost always those who give not those who take. Have you noticed that the “famous” people who are out there trying to make the world a better place rarely wind up in rehab?

The side effects of this celebrity-obsessed culture are frustration and loneliness. Not everyone can be famous, but our culture seems to imply otherwise. With people fixating over the amount of Facebook likes they receive, real values are lost and comparisons are hugely debili-tating. Pastor and author Steven Furtick points out that “When we look at someone’s Facebook page we are comparing our behind the scenes with other people’s highlight reels.” Craig Groeschel, founder of the Life Compass churches agrees: “While we wrestle with our flaws and inadequacies we are looking at images that have been photoshopped and cropped, filtered and edited. What we see online makes our own reality seem dingy and dull.

As our culture generates its endless images, we are fed more and more information about people who are less and less real. There is increasingly tight control of the image by the image makers—the publicists, managers, and agents behind the scenes. Press agents and publicists arrange the locations of interviews, channel the discussion into approved areas, and influence a magazine’s selection of a writer by refusing to cooperate with any scribe they feel will not benefit the celebrity. A media outlet that publicizes scathing information about a star risks alienating a publicist who controls an entire stable of stars.

The same control is exercised over photos, as well as copy. For years Rod Stewart’s manager would not allow him to be photographed unless there was a beer or other form of alcoholic drink in the photograph. It didn’t matter where or when you interviewed him, the drink had to be in the shot. Celebrities control photo shoots far more now than a decade ago, reports Mitch Gerber, a paparazzo who specializes in long-lens surprise shots of celebrities. “It’s not like it used to be. Years ago people didn’t care if you took photos of them eating or blowing their nose. Now they’re cautious because of all the TV shows and news magazines out there. Stars don’t want to be caught in real-life situations. I tried to sell long-lens photos of Michael J. Fox with his sons, and two magazines said if they were to publish them, they would never get a photo with Fox again. The big-shot celebrities are all doing that now.”

The same control is exercised over photos, as well as copy. For years Rod Stewart’s manager would not allow him to be photographed unless there was a beer or other form of alcoholic drink in the photograph. It didn’t matter where or when you interviewed him, the drink had to be in the shot. Celebrities control photo shoots far more now than a decade ago, reports Mitch Gerber, a paparazzo who specializes in long-lens surprise shots of celebrities. “It’s not like it used to be. Years ago people didn’t care if you took photos of them eating or blowing their nose. Now they’re cautious because of all the TV shows and news magazines out there. Stars don’t want to be caught in real-life situations. I tried to sell long-lens photos of Michael J. Fox with his sons, and two magazines said if they were to publish them, they would never get a photo with Fox again. The big-shot celebrities are all doing that now.”

“In an increasingly complicated world,” notes USC’s Braudy, “we personalize our understanding of life. That’s why biography has become a major genre over the past few decades, and why in journalism everybody from the New York Times on down starts a story—even one about ideas or policies—with an anecdote of some sort. It’s part of the relentless personalization of our society.”

There are many harmful ways people try to get their name in the news. It is mind-blowing how many 15-minutes-of-fame reality-TV stars have gone on to pose for Playboy, released a sex tape, or just straight-up started starring in porn. Perhaps they truly get joy and self-worth from putting their bodies out there for public consumption, but for most of them it is a last-ditch effort to keep themselves relevant, even if they have to do something they never thought they would. In a world where we accept that anyone can become a celebrity for any reason, a lot of people have discovered they are famous for the wrong one. Ask the dentist that shot Cecil the lion. He had the correct permit to go big-game hunting, just like dozens of other people every year, but because he shot the wrong one he became an Internet celebrity. He also received hundreds of death threats and had to close his practice for weeks. Once you become famous online. it is a free-for-all. It doesn’t matter if you were a private citizen before that; now society owns you and usually will not be kind. America is really, really good at churning out celebrities. And our actors and singers become famous around the world at a rate no other country can match. But we expect a lot from people whom we build up to those heights. Namely, that you be perfect all the time. A hint of scandal and we are more than happy to tear you down. The gossip trade is a $3 billion a year industry. That’s “billion,” with a B. And no one wants to read about how great famous people are. They are already richer and more attractive than we are, so give us some good schadenfreude (delight in another’s misfortune). We want to see these seemingly perfect people fall.

Then there are the people we love to hate. The Kardashian family did not become as successful as they are today because everyone was ignoring them. But because we don’t really think they deserve their fame, we are willing to believe almost any terrible thing about them. For example, when Lamar Odom was rushed to the hospital a few weeks ago, members of his estranged wife’s family hurried to be by his side. And if you believe this Radar Online headline, they did so with cameras in tow, all ready to film that human tragedy for their TV show. It didn’t matter that E! completely denied this; Radar still kept the article up and people continued to believe it because it seemed like something those fame-whores would do.

We’ve all read interviews with celebrities in which they whine about being famous, where they say that they wish they could just go grocery shopping again without being recognized. And while it might seem ridiculous to us that they are complaining about achieving something that so many other people want and that comes with so many amazing perks, they have a point. Fame has almost never made anyone happy. A study on the different stages of being famous found that celebrities experience extreme emotions like addiction to their fame, a loss of self, and a general sense of mistrust of those around them.

As Kathy Bejamin said in her Weird World blog, “We have to stop obsessing. If we’re starting at 5 years old and only finally giving up on our deathbeds, we are wasting our lives chasing a dream that is not only hurting society but wouldn’t make us happy even if we caught it.”

Watching reality shows based on rather average, albeit amusing, people makes us feel that we are somehow less than them. On reality television, narcissism and self-importance is rampant. The “look at me” culture of today is probably best exemplified by the infamous selfie, and, while drawing attention to oneself can seem harmless, exhibitionism and extreme behavior, in the name of fame, can be harmful and dangerous. Some people will stop at nothing in order to become famous. To attain even a small degree of personal celebrity you have to have certain characteristics. People who amass a large number of friends on Facebook generally know how to get people to like them. They are social creatures. Much of the recognition given to You Tube films is based on their being clever or displaying some unique skill. What if a person is not sociable or clever and doesn’t have any unique skills? He or she can still draw attention to themselves by saying or doing outrageous things. Unfortunately, it is easier to get attention by saying or doing negative things than positive ones. But, even if you succeed in acquiring a little personal celebrity, it will soon becomes dissatisfying. After a while people start to feel that they can’t go without the reassurance that tiny amount of personal celebrity gives them. They need more followers, more “fans,” because they have to get their daily dose of attention. And, for some people, keeping fame limited to a few thousand people online stops being enough. They need to bring it into the real world. For some people this could be as simple as taking the songs they posted on YouTube and start singing them at open mic nights. But there are people out there who want to be famous but have no talents. They can’t ignore the signs that society gives them that fame is the ultimate measure of success. And we as a society don’t care if they get famous for being good or bad; we’ll still put their face on the cover of People.

Researchers are now saying that one of the reasons America has so many mass shootings is because of the emphasis we put on fame. We see it all the time in the manifestos left behind by these shooters: They all want to surpass Columbine in infamy and body count, they want to be plastered on the news, and they want to become a household name. And it is only very, very recently (like, within the last year) that media outlets are learning to not give in to these desires. But as long as even one news channel concentrates on the killer, the need for a sick kind of fame will still motivate these people. Assassinations are often driven by the same reasons. According to a study of people who have tried to kill politicians, it usually has nothing to do with politics and everything to do with getting people to notice them after a lifetime of being invisible. One guy who attempted to assassinate a vice president said he thought he might get a “whole chapter” in the history books for that.

Another sad result of the publicity generated around such attacks is that several mass murderers have actually studied the account of previous killers in order to perfect their own plans for murder. Sometimes they are even inspired by them. Seung-Hui Cho, the Virginia Tech shooter repeatedly mentioned Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the Columbine shooters, in his manifesto, at one point even referring to them as “martyrs”.

The Pressure of Consumerism

Because of the pressures of consumerism, virtually everyone in America wants more than they have and, sadly, often purchases more than they can afford. Advertising companies spend billions making people think luxuries are necessities. Wealth is so common and so flaunted in America that many people feel entitled to it – and a great many feel like failures when they don’t have it. American workers, feel a constant pressure to earn more money. For many men, since they are traditionally expected to be the income provider for the family, this leads to a feeling I like to call “The Squeeze”. With every new product they can’t afford the squeeze becomes tighter. If they can’t afford to send their kid to the private school the family wants for him, the squeeze gets even tighter. The tighter the squeeze, the more escapes are needed which often lead to drinking, drugs or affairs. If and when the wife and kids leave you would think the pressue of the squeeze would leave with them, but it doesn’t. Instead guilt and loneliness are added to the weight and the pressure gets even tighter. The truth is some people can handle the squeeze as part of everyday life, but other people simply cannot. When those people are squeezed too tight, they pop! Sometimes they run away, sometimes they kill themselves and sometimes they kill others. Most of the mass murders in America involve one guy losing it and killing three or four people. It may be his family or it maybe people at his workplace or it may be the church, the library or the mall. Nearly every day I read about some guy popping. They are popping all over the country and the squeeze is one of the reasons it’s happening in America.

Capitalism is the greatest economic system in the world because it provides the most freedom, but there is a natural downside to it. The goal is always to make more money. If you are a stockholder in a major corporation yo want the profits to keep going up. If the company made profits of ten million dollars, the stockholders want the company to make more than a ten million dollar profit this year and they will pressure the board and the board will pressure the president of the company to do exactly that. There is no standing still. Even if you are making money there is always pressure to make more. It’s the same in every industry and pretty much the same for every individual. When Michael Jackson sold 23 million copies of the Thriller album there were people around him who said, “Yeah, that was great. Buy you can do better. You can sell more!” And that’s how it is. This is the downside of the system and it leads to things like tobacco companies selling their product long after they knew it was killing people, beer companies marketing to underage kids even when they know that alcohol is involved over half the time in the four leading causes of teen death – auto accidents, drownings, suicides and murders.

Capitalism is the greatest economic system in the world because it provides the most freedom, but there is a natural downside to it. The goal is always to make more money. If you are a stockholder in a major corporation yo want the profits to keep going up. If the company made profits of ten million dollars, the stockholders want the company to make more than a ten million dollar profit this year and they will pressure the board and the board will pressure the president of the company to do exactly that. There is no standing still. Even if you are making money there is always pressure to make more. It’s the same in every industry and pretty much the same for every individual. When Michael Jackson sold 23 million copies of the Thriller album there were people around him who said, “Yeah, that was great. Buy you can do better. You can sell more!” And that’s how it is. This is the downside of the system and it leads to things like tobacco companies selling their product long after they knew it was killing people, beer companies marketing to underage kids even when they know that alcohol is involved over half the time in the four leading causes of teen death – auto accidents, drownings, suicides and murders.

The truth is that teenagers buy 30% of the beer sold in America and, despite the “Drink Responsibly” tags on some beer commercials, the commercials are targeting kids. Richard Kiel, the giant sized actor who played “Jaws”, the James Bond villain with the mental teeth, told me he was approach by a beer company to do an ad because of his “huge popularity with 12 to 15 year old boys. When he turned down the offer, the beer company doubled it and when he turned it down again, they doubled it again. He refused the commercial because he didn’t want to be part of turn kids into alcohols. If a boy has his first beer at age 12, there is a 40% chance he will become an alcoholic at some point in his life.

Summary

These five factors – Access to Guns, Familiarity with Violence, The Pressure of Consumerism, Lack of Proper Mental Health Treatment and The Culture of Fame form a deadly combination that is both uniquely American and almost impossible to stop. It is a perfect storm for spontaneous incidents of mass murder. In my book I offer what I think might be some solutions to the mass murder crisis in America, but they require a unified approach and sacrifice that, frankly, I don’t think Americans are willing to make.

No Comment