New X-Ray Technique Reveals Mummy Under Wraps : A Well Thought Out Scream by James Riordan

The primary problem in trying to study a mummy is that if you take the wrappings off, the body disintegrates before you can do much examination. The idea for using a high-energy particle accelerator for the examination came after one of the co-curators, Essi Rönkkö, stumbled upon a fully intact mummy, with portrait still attached, at the Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary on the Northwestern campus.

“We had a whole intact mummy right here on campus,” Marc Walton, a materials scientist at Northwestern, said. “The museum community didn’t know it was there.” A wealthy Chicago family, the Hibbards, had financed Egyptian excavations in the early 20th century and received the mummy as a gift, which they donated to the theological seminary.

In a stroke of luck, the mummy originated from the same region of Egypt as the portraits that the team had already been collecting for the exhibition.

The Hibbard mummy contains the body of a young Egyptian girl, estimated to be around 5 years old when she died at the end of the first century A.D. She lived in an agricultural community west of the Nile, and likely died of a disease like smallpox or malaria.

The mummy is noted for its “embedded portrait,” a realistic-looking face painted onto a wood panel rather than sculpted into a facade like mummies in popular culture. That portrait, along with the fact that the mummy was fully intact, was what first caught the attention of one of the seminary collection’s curators and resulted in the research team studying it with the particle accelerator.

The “embedded portrait.” Northwestern University

Walton and a colleague from the classics department, Taco Terpstra, enlisted the help of undergraduate and graduate students in analyzing the mummy’s material makeup with a variety of specialized scans.

Olivia Dill, a first year art history Ph.D. candidate, is helped conduct a CT scan of the Hibbard mummy to discern how she died. With no visible injuries, the researchers think the girl likely succumbed to a disease, such as smallpox or malaria.

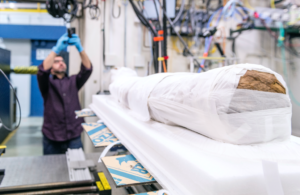

Researchers temporarily removed the mummy from its home in a collection at the Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary at Northwestern University and brought it to the Argonne National Laboratory, located just outside Chicago. There, they used the Advanced Photon Source—the brightest X-ray source in the Western hemisphere—to look inside without risking any damage.

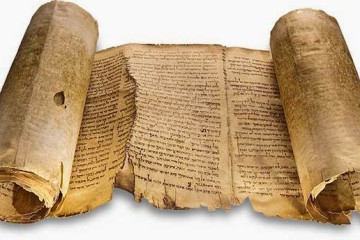

Archaeologists have used X-rays before. In 2016, Wired reported that X-rays were allowing researchers to read ancient texts that had been buried inside mummy-containing coffins. High-definition CT scans have been used to look at mummies too. This, however, is the first time a high-energy particle accelerator, which is usually intended for physics-based research as opposed to medical or biological, has been used to look at mummified remains.

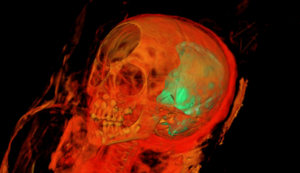

According to an Argonne National Laboratory press release, the mummy weighs about 50 pounds. It also contains more than just the girl’s remains.  The scientists aren’t sure what the object placed in her skull was used for. Northwestern University

The scientists aren’t sure what the object placed in her skull was used for. Northwestern University

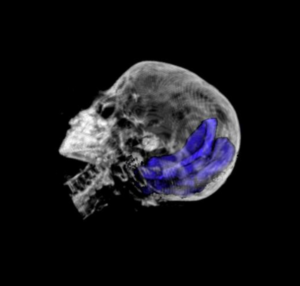

But the CT scan revealed other hidden secrets. Wrapped to the little girl’s belly was some kind of small object.

“The resolution on the CT scan is such that we can only barely make out a shape. We think it’s some sort of stone, but we’re not sure,” Olivia Dill, a first year art history Ph.D. candidate who helped conduct the scan, told PBS NewsHour.”

Dill is most excited about examining the two dozen small pins inserted into the wrappings around the feet and head of the mummy. It is unclear “whether they are modern additions possibly due to conservation efforts or if they are contemporary to the rest of the mummy,” Dill said. “We’re hoping that the analysis at the Argonne lab will enable us to identify the material a little more specifically.”

The X-ray allowed researchers to examine the rich assortment of objects that had been buried inside along with the girl’s body. Shards, possibly from a bowl-like object made of tar (as opposed to glass) had been placed inside her skull after the brain was removed during the mummification process. Wires, the nature of which are unknown, were found in her teeth. And a small, mysterious object had been wrapped to her stomach.

The Advanced Photon Source facility of Argonne National Laboratory speeds up electrons along a 3,600 foot circular track to produce high energy x-rays. These beams are used for high-resolution imaging of various materials, from pharmaceutical to microelectronics.

The Advanced Photon Source facility of Argonne National Laboratory speeds up electrons along a 3,600 foot circular track to produce high energy x-rays. These beams are used for high-resolution imaging of various materials, from pharmaceutical to microelectronics.

Walton and company opted for this particle accelerator scan because it not only reveals material composition, but characteristics like density and shape — without physically altering the mummy. Archaeologists have employed the Advanced Photon Source in the past, but never for mummified remains, the team said.

After working through the night, Stuart Stock, a cell and molecular biologist at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University who led the Advanced Photon Source experiment, shared some preliminary findings with the NewsHour.

Northwestern University’s Hibbard mummy lived during the late first century A.D. Her home was located in an agricultural community in the Faiyum oasis just west of the Nile, at the crossroads of a fading Egyptian and growing Roman empire. And recently a team of scientists carted her off for a 24-hour session with the particle accelerator. The experiment at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory used high energy X-rays to further probe the material composition of numerous objects embedded deep inside the mummy without damaging its remains. This is a far cry from the mummy unwrapping parties that were popular in Victorian England when Egyptomania gripped the nation in the 19th century. Performed in the name of science and entertainment, those crude experiments tore into mummies, destroying many specimens in the process. But times have changed, and so has technology.

Northwestern University’s Hibbard mummy lived during the late first century A.D. Her home was located in an agricultural community in the Faiyum oasis just west of the Nile, at the crossroads of a fading Egyptian and growing Roman empire. And recently a team of scientists carted her off for a 24-hour session with the particle accelerator. The experiment at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory used high energy X-rays to further probe the material composition of numerous objects embedded deep inside the mummy without damaging its remains. This is a far cry from the mummy unwrapping parties that were popular in Victorian England when Egyptomania gripped the nation in the 19th century. Performed in the name of science and entertainment, those crude experiments tore into mummies, destroying many specimens in the process. But times have changed, and so has technology.

“Our main motivation is to use the physical sciences to be able to unpack the technology of art,” Marc Walton, a materials scientist at Northwestern and one of the project’s leaders, told PBS. “We’re trying to get into the mind of the artist to understand why they’re making certain choices based upon the economics of the materials, their physical structure, and then use that information to be able to rewrite history.”

A reconstruction of the bowl-shaped object in the Hibbard mummy’s skull. Photo by Northwestern Memorial Hospital

“The shards within the skull do not show any evidence of crystallinity,” Stock said. “I am inclined to think the shards are something noncrystalline like solidified pitch,” meaning the shards came from a thick organic material like tar and not from something fragile like glass, which has a crystal structure.

Stock also found fine wires were embedded in the mummy’s teeth, but their composition remains unknown. As for the other objects, Stock said he “can’t say much yet about the inclusions within the wrappings”

All this experimentation is helping narrow down the materials used by these cultures. For example, other mummy portraits contain red pigment from lead found in Spain, painted on a type of wood that grows in central Europe–physical proof that trade was flourishing across the vast Roman empire. The students have been analyzing the mummy’s portrait in this context while also running various tests on the mummy itself.

“Our main motivation is to use the physical sciences to be able to unpack the technology of art,” said Marc Walton, a materials scientist at Northwestern University and a leader of the project. “We’re trying to get into the mind of the artist to understand why they’re making certain choices based upon the economics of the materials, their physical structure, and then use that information to be able to rewrite history.”

Instead of a golden, idealized, three-dimensional face akin to King Tut’s sarcophagus, the Hibbard mummy has a more photorealistic representation of the girl’s face painted onto a wood panel.

These wood panel paintings, called mummy portraits, represent the largest surviving collection of paintings from antiquity. Preserved by the dry Egyptian climate, thousands of these mummy portraits have been found, but only a small fraction remain intact with their mummy.

Hibbard mummy at the Advanced Photon Source. Photo by Northwestern University

The added benefit of these cutting-edge tools is their non-invasive nature–a mummy can be analyzed without unwrapping it. Many mummies were lost to the fad of unwrapping parties in Victorian England, when Egyptomania was sweeping the nation. Little attention was paid to the religious and cultural implications of disturbing what are, at the end of the day, human remains.

“It’s a person who has been prepared for burial in a very specific and very careful way to ensure a successful afterlife,” Dill said. “Learning that through this project and this class has been very humbling and touching.”

By using these noninvasive scientific instruments, art historians can make sure they are respecting mummified remains while sharing that humbling joy of discovery for generations to come.

No Comment