Chicago Retains “Murder City” Title Through First Half of 2017 : A Well Thought Out Scream by James Riordan

Chicago’s long time designated nick-name as the Windy City has been replaced in many instances with the moniker “Murder City” or “Chiraq”. Though far from ranking as the nation’s murder capital on a per-capita basis, Chicago is the runaway leader in total killings and shootings. For yje first half of 2017 Chicago had fifty more homicides than New York and Los Angeles combined, even though it is far less populous than both.

At the year’s midpoint, 320 people have died in Chicago violence — only two fewer homicides than the previous year. With most of the summer still ahead, the city is on track to top 700 homicides for a second consecutive year, a mark that had otherwise not been reached in two decades. Many young blacks refer to America’s third largest city Chiraq because more murders and violence occurs in Chicago than the war in Iraq. They claim that walking the streets of Chicago is like walking in Iraq with all the murders, robbery, gang bangs, and acts of violence. The nickname has become so popular that film director Spike Lee chose it as the title of his 2015 film, a satirical musical drama directed and produced by Lee and co-written by Lee and Kevin Willmott. Chiraq is set in Chicago and the film focuses on gang violence in the city’s south side, particularly the Englewood neighborhood. While I can’t recommend the film due to its explicit scenes of sex and violence, it is a clear indication of how Chicago is viewed by the public at large.

Chicago Police are pretty much overwhelmed, but police Superintendent Eddie Johnson has implemented several new measures. The increased violence comes at a daunting time for the Police Department as it continues to cope with the fallout 19 months after the court-ordered release of a video of a white officer shooting black teen Laquan McDonald 16 times. The video touched off angry, prolonged protests and a U.S. Department of Justice investigation that found Chicago police to be badly trained, lackadaisically supervised, rarely disciplined and prone to using force, particularly against minorities. The unprecedented crisis led to concerns that demoralized officers had pulled back on their aggressiveness, contributing to the surge in violence last year in particular.

Superintendent Johnson has said he believes the furor over the shooting — as well as what he called a national “anti-police narrative” resulting from a series of other high-profile shootings by police — has emboldened criminals in Chicago who think officers are lying low over fears of being sued, disciplined or even indicted. “I do believe that they suspect that the police are on their heels and the police were going to be less aggressive because of the things that are going on,” said Johnson, who was named superintendent more than a year ago after predecessor Garry McCarthy was fired amid the McDonald video fallout.

Superintendent Johnson has said he believes the furor over the shooting — as well as what he called a national “anti-police narrative” resulting from a series of other high-profile shootings by police — has emboldened criminals in Chicago who think officers are lying low over fears of being sued, disciplined or even indicted. “I do believe that they suspect that the police are on their heels and the police were going to be less aggressive because of the things that are going on,” said Johnson, who was named superintendent more than a year ago after predecessor Garry McCarthy was fired amid the McDonald video fallout.

Indeed, street stops plunged last year after a state law required officers to more thoroughly document who they stopped and why. So far this year, street stops have continued to drop, though more modestly — to 51,002 as of June 19, down 3.7 percent from a year earlier.

Chicago Police Department Superintendent Eddie Johnson speaks during a news conference in Chicago

That sharp drop-off over the last 18 months has not concerned Johnson, who reiterated in the interview that “quite frankly, we probably were stopping people that we shouldn’t have been stopping.” In an interview at his fifth-floor office at police headquarters, police Superintendent Eddie Johnson said he’s focusing on reducing the city’s shootings, with the belief that curbing violence depends on stemming gunfire, not trying to control its aftermath. He pointed to a double-digit drop in shootings so far this year as a sign of real progress in the Police Department’s efforts.

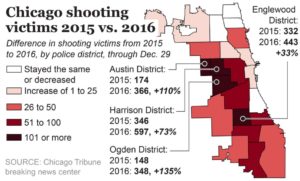

The number of shooting victims indeed dropped 14 percent from the first half of 2016, yet the total remains painfully high. This year’s shooting toll is hundreds more than in the first six months of 2013, 2014 and 2015, the department’s own numbers show. While a new police initiative in Chicago’s two historically most crime-plagued districts shows early promise, violence remains high as the city marks the often turbulent July Fourth weekend. Johnson lauded the early improvements seen in the city’s historically two most violent districts — Harrison, which includes the East and West Garfield Park neighborhoods and part of North Lawndale on the West Side, and Englewood, which covers both the Englewood and West Englewood neighborhoods on the South Side. Together, those two districts accounted for about one-fourth of all Chicago homicides last year, a figure that had dropped to about 19 percent so far this year.

The number of shooting victims indeed dropped 14 percent from the first half of 2016, yet the total remains painfully high. This year’s shooting toll is hundreds more than in the first six months of 2013, 2014 and 2015, the department’s own numbers show. While a new police initiative in Chicago’s two historically most crime-plagued districts shows early promise, violence remains high as the city marks the often turbulent July Fourth weekend. Johnson lauded the early improvements seen in the city’s historically two most violent districts — Harrison, which includes the East and West Garfield Park neighborhoods and part of North Lawndale on the West Side, and Englewood, which covers both the Englewood and West Englewood neighborhoods on the South Side. Together, those two districts accounted for about one-fourth of all Chicago homicides last year, a figure that had dropped to about 19 percent so far this year.

Beginning in late January, those two were the first districts to use technology designed to help officers better predict where shootings may occur, respond more quickly to violence and allow supervisors to analyze shooting data in real time to quickly determine where to best deploy manpower.

At these district nerve centers, called Strategic Decision Support Centers, officers analyze large TV screens that display crime maps and surveillance camera footage. They also keep a close watch on ShotSpotter technology that captures the sound of gunfire and helps pinpoint its location. Officers receive the shooting data in real time on their work cellphones.

At these district nerve centers, called Strategic Decision Support Centers, officers analyze large TV screens that display crime maps and surveillance camera footage. They also keep a close watch on ShotSpotter technology that captures the sound of gunfire and helps pinpoint its location. Officers receive the shooting data in real time on their work cellphones.

Through June 25, shooting incidents in the Harrison District dropped to 152, a 34 percent decline from 229 a year earlier, department statistics show. Homicides fell less sharply, to 31, down 18 percent from 38 a year earlier. Remarkably, over the Memorial Day weekend, not a single shooting took place in the entire district, a dramatic improvement from a year earlier.

In the Englewood District, by comparison, homicides fell to 28, down 28 percent from 39 a year earlier, while shooting incidents dropped 31 percent, to 104 from 150, according to the department records.  Johnson largely attributed the reduction in violence to the new crime-fighting technology. He noted how many minutes can elapse from the time a resident hears a gunshot, calls 911 and a dispatcher takes down the information and alerts patrol officers. With the ShotSpotter data, officers not only learn instantaneously on their smartphones that a shot has been fired, but also its location with pinpoint accuracy, he said.

Johnson largely attributed the reduction in violence to the new crime-fighting technology. He noted how many minutes can elapse from the time a resident hears a gunshot, calls 911 and a dispatcher takes down the information and alerts patrol officers. With the ShotSpotter data, officers not only learn instantaneously on their smartphones that a shot has been fired, but also its location with pinpoint accuracy, he said.

That has dramatically improved response time to 911 calls, the department said. In Harrison, officers reached the scene of a 911 call on average in 5.8 minutes as of April, down from 9.6 minutes a year earlier, according to the department. The average response time in Englewood fell to 4.7 minutes, down from 6.1 minutes.

Even more important, Johnson said the technology, which has since been expanded to four additional police districts, allows commanders to make “real-time adjustments” to their deployment, moving additional officers quickly to scenes of shootings.

What once might have taken 24 hours can now be done in five minutes in Harrison and Englewood, Johnson said. The result, he believes, can be particularly effect retaliatory shootings, “We can stop retaliatory shootings before they occur,” he said. “And that has paid off big-time for us in those two districts.”

What once might have taken 24 hours can now be done in five minutes in Harrison and Englewood, Johnson said. The result, he believes, can be particularly effect retaliatory shootings, “We can stop retaliatory shootings before they occur,” he said. “And that has paid off big-time for us in those two districts.”

Johnson acknowledged that Harrison and Englewood typically have added manpower because of the high levels of violence there, another likely factor in the reduced violence.

Research indicates that a complex mix of factors causes the violence. There is little doubt that gang disputes play a huge role causing violence to erupt over everything from petty disputes to control of drug dealing, as well as the splintering of gangs into smaller cliques fighting over a few blocks at a time. Police cite the flow of illegal firearms into the streets and gang conflicts that erupt over social media platforms.

Yet there are deeper societal problems at play as well, including long histories of poverty, joblessness, segregation and neglect in pockets of the South and West sides.  Amid the city’s frustratingly steady gunfire, a few spasms of violence captured major public attention. The first half of the year saw three children killed over just four days, a respected judge gunned down in his Far South Side backyard and the homicides of seven people, including a pregnant woman, in a single day in March in the South Shore community. The fact that shootings are down and homicides are flat overall means little to the families of recent victims.

Amid the city’s frustratingly steady gunfire, a few spasms of violence captured major public attention. The first half of the year saw three children killed over just four days, a respected judge gunned down in his Far South Side backyard and the homicides of seven people, including a pregnant woman, in a single day in March in the South Shore community. The fact that shootings are down and homicides are flat overall means little to the families of recent victims.

While violence fell in Harrison and Englewood, two districts on the South Side have endured their worst violence in several years. In the South Chicago District, which includes the South Chicago and South Shore neighborhoods, homicides doubled to 24 through June 25, a five-year high, official department statistics show. Shootings in the district also jumped 40 percent to 87 from 62.

In the Calumet District, which covers the Roseland and West Pullman neighborhoods, homicides more than doubled to 21 from 9 a year earlier, a five-year high, according to the department. Shootings, though, fell to 79, an 8 percent decline from 86 a year earlier.

Johnson blamed gangs “at war” for the increased violence in South Chicago, but he offered no explanation for Calumet.

Parts of the South Chicago District have long been beset by violence, much of it stemming from conflicts between factions of the Black P Stones and Gangster Disciples. Gang woes have long been an issue in the Calumet District as well, according to veteran cops.

Parts of the South Chicago District have long been beset by violence, much of it stemming from conflicts between factions of the Black P Stones and Gangster Disciples. Gang woes have long been an issue in the Calumet District as well, according to veteran cops.

Criminologists caution against making comparisons in crime statistics month to month or even year to year, arguing that long-term trends give a truer picture of how violence changes over time.

Richard Rosenfeld, a criminology professor at the University of Missouri at St. Louis, said the opioid epidemic could be a factor driving Chicago’s homicide increase over the last 18 months, saying it has caused a greater demand for heroin on the street.

“As those markets expand, they entice more sellers into the market, and that means more disputes among sellers and between buyers and sellers, and that can result in violence, including homicide,” he said.

Chicago police highlighted the link between drugs and violence earlier this year with maps displaying how the locations of shootings and drug overdoses overlapped. The maps showed a high concentration of shootings and overdoses happening on the West Side near the Eisenhower Expressway, dubbed the “Heroin Highway” because of the easy access it provides for drug-buying suburbanites.

Rosenfeld also said he believes the fallout from the Laquan McDonald shooting could still be contributing to the heightened violence, noting how the episode has exacerbated an already tense relationship between the police and minority communities. “They’re less likely to report a crime to the police when they witness a crime or have information about a crime, less likely to cooperate with the police in an investigation and more likely, when disputes arise, to take matters into their own hands, and that too can give rise to violence,” he said. “I think that’s what’s happening in Chicago right now.”

Experts say the great amount of guns and the’ easy access to them have long been major contributors to Chicago violence as well. While conceding officers were “more cautious and careful about what they were doing,” Johnson expressed confidence that they weren’t sitting on the sidelines, saying a rise in gun arrests is a better barometer of the dangerous work they continue to do every day. As of June 19, those arrests had risen to 1,974, a 30 percent increase from 1,516 a year earlier, according to department figures. Johnson said the rise in gun arrests shows “we’re arresting the right people for the right reasons.”

While many gang members can’t buy guns legally because of their criminal records, they have plenty of alternatives, including with gun shows and dealers operating under less stringent laws just a short drive away in northwest Indiana. Gang members can also find legal buyers to purchase firearms for them at gun shops in the suburbs and downstate — an illegal practice known as “straw purchasing.”

The extent of the problem, Johnson said, can be seen in the wide disparity between how many of Chicago’s homicide victims were slain by gunfire as compared to other big cities.

For the first six months of 2017, more than 90 percent of Chicago homicide victims were slain by gunfire, according to Police Department records. But in New York City, only about 49 percent of homicide victims were the victims of gun violence. According to a study released in January by the University of Chicago, 72 percent of Los Angeles’ homicides in 2016 were with a gun.

“Everyone in the city recognizes that it’s the gun violence that is the No. 1 public safety priority,” said Jens Ludwig, one of the authors of the study and the director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab.

“Everyone in the city recognizes that it’s the gun violence that is the No. 1 public safety priority,” said Jens Ludwig, one of the authors of the study and the director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab.

Johnson had long been pushing for tougher sentences for repeat gun offenders, saying they were responsible for much of the bloodshed. In spite of the long-running gridlock in Springfield, legislation backed by Johnson and Mayor Rahm Emanuel was signed into law June 23. It potentially doubles prison terms for repeat gun offenders.The law, which takes effect next January, “will have an impact,” Johnson said, but more needs to be done. “We haven’t created that culture of accountability,” he said. “But we’re getting there, we’re getting there.”

___

No Comment