It Ain’t Easy Being Bob : A Well Thought Out Scream by James Riordan

This week we are republishing this year’s most popular blog which was on Bob Dylan accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature back in March.

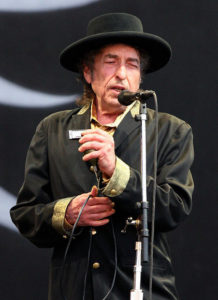

Last week Bob Dylan performed in Stockholm and while he was there he met with the Nobel Prize Committee and accepted this year’s award for literature. Klas Ostergren, a member of the Swedish Academy, said the 75-year-old American singer-songwriter received his award during a small gathering Saturday afternoon at a hotel next to the conference center where Dylan was performing a concert later that night. Ostergren told The Associated Press that the ceremony was a small, intimate event in line with the singer’s wishes, with just academy members and a member of Dylan’s staff attending. “It went very well indeed,” he said, describing Dylan as “a very nice, kind man.” Other members of the academy told Swedish media that Dylan seemed pleased by the award.

During his show hours later, Dylan made no reference to the Nobel award, simply performing a set blending old classics with tunes from his more recent albums. Dylan had declined the invitation to attend the traditional Nobel Prize banquet and ceremony on Dec. 10 — the date of Alfred Nobel’s death —pleading other commitments. But in order to receive the award worth 8 million kronor ($894,800), Dylan must give a lecture within six months from Dec. 10. He has said he will not give his Nobel lecture this weekend but a recorded version of it will be sent later. Taped Nobel lectures have been occasionally presented, most recently in 2013 by Canadian Nobel literature laureate Alice Munro.

The 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” He had expressed awe at receiving the Nobel Prize and thanked the Swedish Academy for including him among the “giants” of writing. Nobody ever had more to say than Dylan even though he spent much of his career denying it. I can understand that. After all it’s hard to live up to the title “Voice of a Generation”. It’s particularly hard when that generation is THE generation – the baby boomers who turned pop culture into high art and looked closely at both the sincerity and inner meaning of everything. When I was in college nearly everyone who had a stereo had a part time hobby of trying to decipher Dylan lyrics like the following:

You used to ride on the chrome horse with your diplomat Who carried on his shoulder a Siamese cat Ain’t it hard when you discover that He really wasn’t where it’s at — Like A Rolling Stone

The beauty of it was that there was no wrong answer especially since Bob was nearly always mum on the subject. It was like he thought his words were clear as a bell and if you couldn’t understand them you must not be listening close enough. Of course later we learned that much of mystery of Bob lyrics and those of other symbolic lyric writers at the time like John Lennon was that “it rhymed”. Often it was about the flow, but it’s important to note that it was the flow that made the lines we could understand resonate so clearly:

Come senators, congressmen, please heed the call Don’t stand in the doorway, don’t block up the hall For he that gets hurt will be he who has stalled There’s a battle outside and it is ragin’ It’ll soon shake your windows and rattle your walls For the times they are a-changin’ — The Times They Are A-Changing

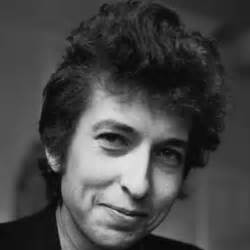

Bob Dylan has been a major figure in music for five decades. In the 1960’s he became a somewhat reluctant leader of the protest movement. Bob was just saying what he thought needed to be said but the disgruntled American youth and those few adults who sympathized with them made his songs anthems to be sung at Civil Rights rallies and chanted at anti-war marches. But Dylan wasn’t all political by any means. He was a philosophizer who gushed forth literary influences and he wasn’t afraid to go against the grain. While most recording artists were singing about their girlfriends Dylan was lamenting the murder of Black Panther leader George Jackson in San Quentin Prison or what he believed was the unjust imprisonment of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. There are a lot of thing one can criticize about Dylan but playing it safe was never one of them.

Robert Allen Zimmerman was born in Duluth, Minnesota at St. Mary’s Hospital on May 24, 1941, but when he was six his father was stricken with polio and the family moved to his mother’s hometown, Hibbing, Minnesota. Hibbing is on the Mesabi Iron Range west of Lake Superior and, as you can imagine, there’s not a whole lot to do there. Bob spent much of his youth listening to the radio, the blues and country stations out of Shreveport and thenrock and roll out of Chicago. While he attened Hibbing High School he formed several bands including the short lived Shadow Blasters and more popular Golden Chords which performed covers of popular songs. Their performance of “Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay” at their high school talent show was so loud that the principal cut the sound off. It would be the first of many such hurdles for young Bob Zimmerman.

In September 1959, Robert Zimmerman enrolled at the University of Minnesota where he really began to discover American folk music. In 1985, Dylan explained the attraction that folk music had exerted on him: “The thing about rock’n’roll is that for me anyway it wasn’t enough … There were great catch-phrases and driving pulse rhythms … but the songs weren’t serious or didn’t reflect life in a realistic way. I knew that when I got into folk music, it was more of a serious type of thing. The songs are filled with more despair, more sadness, more triumph, more faith in the supernatural, much deeper feelings.” He soon was performing at the 10 O’clock Scholar, a coffee house a few blocks from campus, and became involved in the what was called the Dinkytown folk music circuit, It was during this time that he began introducing himself as “Bob Dylan”. In his autobiography, Dylan acknowledged that he had been influenced by the poetry of Dylan Thomas explaining his name change in a 2004 interview, “You’re born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself. This is the land of the free.”

Dropping out of college in January, 1961 at the end of his freshman year, Dylan travelled to New York City hoping to perform there and visit his musical idol Woody Guthrie, who was seriously ill in Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital with Huntington’s Disease. Guthrie was Dylan’s biggest influence especially in his early years. Dylan later wrote about Guthrie, “The songs themselves had the infinite sweep of humanity in them … [He] was the true voice of the American spirit. I said to myself I was going to be Guthrie’s greatest disciple.” It was here that Dylan meant another key influence and Guthrie disciple, Rambling Jack Elliot. I met Rambling Jack one time. He was walking (rambling) down Pacific Coast Highway for some reason and I was doing the same. He was a nice guy. As authentic as it gets.

In early ‘61 Dylan played often around the Greenwich Village area of New York. He got noticed by New York Times critic Robert Shelton for a show he did at Gerde’s Folk City and noty long after he met Columbia Record’s producer John Hammond who signed him to the label. Bob’s first album sold only 5,000 copies the first year it was out and people at Columbia started calling Dylan “Hammond’s Folly” but Hammond vigorously defended him to the label. In August of 1962 Dylan signed with Albert Grossman who managed him for nearly a decade. Of Grossman Dylan later said, “He was kind of like a Colonel Tom Parker figure … you could smell him coming.” When Grossman and John Hammond clashed, Hammond was replaced by Tom Wilson, a young African American jazz producer for Dylan’s second album.

In May of 1963 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan was released and it attracted many influential listeners including the Beatles’ George Harrison who said, “We just played it, just wore it out. The content of the song lyrics and just the attitude—it was incredibly original and wonderful.” Dylan’s rough sounding singing was unsettling to some but an attraction to others. David Bowie, in his tribute, “Song for Bob Dylan,” described it as “a voice of sand and glue”. Joyce Carol Oates wrote: “When we first heard this raw, very young, and seemingly untrained voice, frankly nasal, as if sandpaper could sing, the effect was dramatic and electrifying.” Many people first embraced Dylan through hearing his songs recorded by more palatable voices such as Joan Baez, The Byrds; Sonny and Cher; The Hollies; Peter, Paul and Mary; The Association; Manfred Mann; and The Turtles. Most of these artists recorded the songs with pop approach and rhythm to the songs that Dylan performed as sparse folk pieces. There were so many recordings of his songs that Columbia promoted the album with the line “Nobody Sings Dylan Like Dylan.”

That same month Dylan walked off the Ed Sullivan Show when the network’s legal people said they were afraid that “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues”, was potentially libelous to the John Birch Society. Soon afterwards Dylan became a prominent figure in the civil rights movement, singing with Baez at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. By “The Times They Are a-Changing, his third album, Dylan was becoming an established voice of protest. Songs like “Only A Pawn In Their Game” about the murder of civil rights worker Medgar Evers and the “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” about the death of black hotel barmaid at the hands of young white socialite William Zantzinger were true stories about real people. At the same time “Ballad of Hollis Brown” and “North Country Blues” discussed the tragedy associated with the decline of farming and mining communities.

That same month Dylan walked off the Ed Sullivan Show when the network’s legal people said they were afraid that “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues”, was potentially libelous to the John Birch Society. Soon afterwards Dylan became a prominent figure in the civil rights movement, singing with Baez at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. By “The Times They Are a-Changing, his third album, Dylan was becoming an established voice of protest. Songs like “Only A Pawn In Their Game” about the murder of civil rights worker Medgar Evers and the “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” about the death of black hotel barmaid at the hands of young white socialite William Zantzinger were true stories about real people. At the same time “Ballad of Hollis Brown” and “North Country Blues” discussed the tragedy associated with the decline of farming and mining communities.

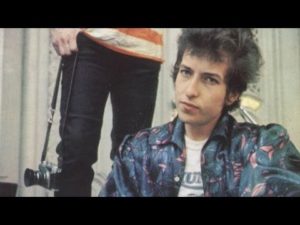

With each successive albums Dylan’s popularity grew. And so did his persona. Sunglasses, pointy Beatle boots, and a Carnaby Street look. One London reporter described him as follows: “Hair that would set the teeth of a comb on edge. A loud shirt that would dim the neon lights of Leicester Square. He looks like an undernourished cockatoo.” But Dylan was not done evolving – not by a long shot. Headlining the Newport Folk Festival in the summer of 1965, Dylan shocked the die-hard folkies by going electric with musicians like guitarist Mike Bloomfield and keyboardist Al Kooper. The lineup was met with some cheering but a great deal of booing and Dylan left the stage after only three songs. He was then roundly criticized by the folk music establishment. In the magazine”Sing Out” Ewan MacColl wrote: “Our traditional songs and ballads are the creations of extraordinarily talented artists working inside disciplines formulated over time… ‘But what of Bobby Dylan?’ scream the outraged teenagers… Only a completely non-critical audience, nourished on the watery pap of pop music, could have fallen for such tenth-rate drivel.” Dylan answered with “Positively 4th Street”, an album filled with scathing lyrics that border on paranoia including the legendary single “Like A Rolling Stone” which, even though it was over six minutes long, reached #2 on the American charts and is credited with changing attitudes in radio and at record labels about what a hit single could be. When Bruce Springsteen spoke during Dylan’s inauguration into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame he said of the song, “that snare shot sounded like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind”. So significant was the effect of “Like A Rolling Stone” that in 2004 Rolling Stone magazine put it at #1 on their list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.”

And so the legend grew. It seemed as though Bob Dylan was the exception to every pop music rule, a true on of a kind. He was even able to avoid the “Curse of 27”, the superstition that at age 27 the greatest rockers must face death. While Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix , Brian Jones, Janis Joplin and a host of others died at that age Dylan faced his near death experience at age 25 and survived, but just barely. On July 29, 1966, Dylan crashed his 500cc Triumph motorcycle on a road near his Woodstock, N.Y. home. His injuries were never fully revealed but Dylan said that he broke several vertebrae in his neck. As usual, with Dylan, the incident swims in mystery since no ambulance was called to the scene and Dylan was not hospitalized. What everyone agrees on is that the recovery period provided him with a much-needed escape from the pressure that had built up around him. Dylan confirmed this in his autobiography when he said, “I had been in a motorcycle accident and I’d been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race.” After the accident, Dylan withdrew from the public eye and, apart from a few select appearances, did not tour again for nearly eight years.

And so the legend grew. It seemed as though Bob Dylan was the exception to every pop music rule, a true on of a kind. He was even able to avoid the “Curse of 27”, the superstition that at age 27 the greatest rockers must face death. While Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix , Brian Jones, Janis Joplin and a host of others died at that age Dylan faced his near death experience at age 25 and survived, but just barely. On July 29, 1966, Dylan crashed his 500cc Triumph motorcycle on a road near his Woodstock, N.Y. home. His injuries were never fully revealed but Dylan said that he broke several vertebrae in his neck. As usual, with Dylan, the incident swims in mystery since no ambulance was called to the scene and Dylan was not hospitalized. What everyone agrees on is that the recovery period provided him with a much-needed escape from the pressure that had built up around him. Dylan confirmed this in his autobiography when he said, “I had been in a motorcycle accident and I’d been hurt, but I recovered. Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race.” After the accident, Dylan withdrew from the public eye and, apart from a few select appearances, did not tour again for nearly eight years.

Of course, the less the pubic saw of Dylan the more they clamored for him and the few appearances he made generated a great deal of publicity. He continued to deliver albums that not only sold well, but, for the most part, always included something unexpected. No one, not record labels, fans, family or the press, has ever been able to box Bob in. In January 1974, Dylan returned to live touring playing 40 concerts coast-to-coast, backed by The Band. In 1975 the success of the phenomenal album, “Blood on the Tracks” spawned the Rolling Thunder Revue tour that featured a wide range of performers including T-Bone Burnett, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Joni Mitchell, David Mansfield, Roger McGuinn, Mick Ronson, Joan Baez, and violinist Scarlet Rivera, whom Dylan discovered walking down the street with her violin case hanging from her back. In November of 1976 Dylan appeared at The Band’s farewell concert, honoring his long relationship with the musicians and much of his set was included in the Martin Scorsese film of the concert, “The Last Waltz”. In 1978, Dylan toured the world performing 114 shows in Japan, the Far East, Europe and the US, to a total audience of two million people.

In 1978, Bob Dylan became a born-again Christian. He was introduced to the faith by fellow musicians T-Bone Burnett, David Mansfield, Larry Myers and Paul Emond. Myers and Emond were assistant pastors at the Vineyard Christian Fellowship in Los Angeles and both Burnett and Mansfield attended church there. I also attended the Vineyard from early 1979 to 1984, after which I attened Jack Hayford’s Church on the Way in Van Nuys, California. I later became good friends with T-Bone Burnett and Larry Myers and I knew David Mansfield, but I did not meet Dylan through them. I met him on my own in a somewhat unique way.

I had just moved to L.A. in November of 1978 and was looking around for a church to attend. I had been born-again in 1976 and attended church regularly before I left Kankakee. This, however, was L.A. which is big, broad and pulls you about twenty different ways at once. A publicist at RSO Records told me about the Vineyard Christian Fellowship, which at that time was located in the San Fernando Valley. I was living in Malibu at the time and it was a good 45 minute trek to the church. Elaine, the girl who told me about the Vineyard, said it was loaded with musicians and other kinds of artists and that Bob Dylan even went to church there. It still took me a month or so to try it out. They had Sunday after-noon services at that time. But on the day we were going to go, my wife felt sick and I had some serious doubts about driving for 45 minutes, through the Sunday beach traffic (which was always heavy in Malibu) and then over the Santa Monica mountains and onto the Ventura Freeway to check out a church I wasn’t sure I would like in the first place. Most things that have a bunch of well known people involved in them tend to be decidedly unspiritual. But, on the other hand, I didn’t even know of any other churches and I’d been putting off what I felt my spirit was telling me to do for several weeks. So I got in my Datsun and headed over the mountains to Reseda alone.

I had just moved to L.A. in November of 1978 and was looking around for a church to attend. I had been born-again in 1976 and attended church regularly before I left Kankakee. This, however, was L.A. which is big, broad and pulls you about twenty different ways at once. A publicist at RSO Records told me about the Vineyard Christian Fellowship, which at that time was located in the San Fernando Valley. I was living in Malibu at the time and it was a good 45 minute trek to the church. Elaine, the girl who told me about the Vineyard, said it was loaded with musicians and other kinds of artists and that Bob Dylan even went to church there. It still took me a month or so to try it out. They had Sunday after-noon services at that time. But on the day we were going to go, my wife felt sick and I had some serious doubts about driving for 45 minutes, through the Sunday beach traffic (which was always heavy in Malibu) and then over the Santa Monica mountains and onto the Ventura Freeway to check out a church I wasn’t sure I would like in the first place. Most things that have a bunch of well known people involved in them tend to be decidedly unspiritual. But, on the other hand, I didn’t even know of any other churches and I’d been putting off what I felt my spirit was telling me to do for several weeks. So I got in my Datsun and headed over the mountains to Reseda alone.

The place was packed and I had looked around and finally found a seat near the back on the left side of the church. I noticed that there were a lot of people in their late 20’s like me, a few older folks and several who were even younger. There was no dress code at the Vineyard and most people wore jeans or shorts. When the service started I was amazed by the lack of pretense. Everything was simple and straight forward and totally sincere. No pomp, no ritual and absolutely no hypocrisy.

Then about ten minutes into the service we sang “Amazing Grace” and I heard this distinct rough edged nasal whine coming from the seat behind me. “Aaaamaaazing Graaace, how sweeeet the sound” the voice sang and I thought, “could this be Bob Dylan?” I had already interviewed lots of rock stars including George Harrison, Frank Zappa, Fleetwood Mac, the Doobie Brothers and many others but I’d never met anyone I truly idolized. Probably because the only people I idolized back then were John Lennon and Bob Dylan, whom no one but the top tier of rock journalists ever got access to and even that was rare. I decided I would sneak a peak so at one point, as I was sitting down, I glance over my shoulder and there he was. It was the classic Dylan image – wild hair, sunglasses and leather jacket. “Yep, that’s him” I thought. Then, later in the service we were asked to greet the people around us. I shook hands with Bob and his black girlfriend, Carol Dennis, whom he later married.

As the service progressed I became very impressed with the pastor whose name was Kenn Gulicksen. Kenn taught with an amazing candidness so different from the churches I grew up in. To use an important phrase from the time, “he told it like it was”, even admitting the things like being in an airport and think about buying a Playboy magazine because, “after all, no one would know” and then chiding himself because “God would know”. Kenn exuded love, kindness and truth and he never put himself on any kind of a pedestal.

As the service progressed I became very impressed with the pastor whose name was Kenn Gulicksen. Kenn taught with an amazing candidness so different from the churches I grew up in. To use an important phrase from the time, “he told it like it was”, even admitting the things like being in an airport and think about buying a Playboy magazine because, “after all, no one would know” and then chiding himself because “God would know”. Kenn exuded love, kindness and truth and he never put himself on any kind of a pedestal.

When the service was over I thought about approaching Dylan, but then held back thinking “I am not going to bother this man at church. He needs to feel that he can come here without that kind of burden. And I didn’t go up to him. He came up to me.

I was in the church bookstore looking around and I happened to pick up a new edition of Hal Lindsey’s The Late, Great Planet Earth, a best selling Christian book of the time that at-tempted to apply bible prophesy to modern times. It was one of my favorite books back then and psrt of the reason I moved to L.A. was because I had this idea about making it into a film. What made this even more interesting was that the man who sat next to me in the pew had given me his card which said that he worked for Hal Lindsey’s company. So I was thinking about that and looking at the book when Dylan approach me and said in his classic drawl, “Hey, that’s a pretty good book, ain’t it?” I said yeah, that I liked it a lot. I thought about telling him of my desire to meet Lindsey and develop a film but then decided to keep silent lest he think I was trying to use him in some way. I mean, here he was, one of the most recognizable people on the planet, venturing out to seek Spiritual growth. I couldn’t bring myself to use that as an opportunity to further my career. But it wasn’t over yet.

Later, I was standing in the parking lot waiting for some cars to go by so I could get to the Datsun and this woody station wagon stopped next to me. It was a new car, but really dusty. The window rolled down and it was Bob Dylan behind the wheel. He said, “Hey, see you next week, huh?”

Now, at this point, I was thinking I would no longer be bothering him since he had approached me twice. So I said, “You know that “Late, Great Planet Earth” book. I just met a guy who works with Hal Lindsey and I’m thinking about going to see him to talk about making a movie out of the book.”

Bob looked at me for a moment and then said, “Can I go with you?”

The surprise and elation I felt was beyond describing. A flood of visions passed through my mind. Me calling up Hal Lindsey’s office and going, “Yes, Bob Dylan and I would like to see you sometime.” I was pretty sure he’d see me. Then the thought of me and Bob working together. Hanging out. And there was Bob, driving a station wagon with the window rolled down, waiting for my response. “Sure, you can go with me.” I told him I lived in Malibu and he said that he did as well which I already knew since his house was like a Malibu landmark. He wrote down his phone number on a torn off piece of paper and told me to give him a call. Then he said goodbye and drove away.

The story behind Bob’s conversion is that he’d been attending Bible study classes at the Vineyard and gotten to know Gulliksen, Myers and Emond. When Myers and Emond visited Dylan in Malibu, he told them he wanted Christ in his life and they prayed with him.

The album that followed Dylan’s conversion was the compelling Slow Train Coming. It won Dylan a Grammy for “Best Male Vocalist” for the song “Gotta Serve Somebody.” While the album sold well Dylan took a lot of heat in the press for his conversion. When he toured from the fall of 1979 to the spring of 1980 Dylan talked about his faith saying things like: “Years ago they … said I was a prophet. I used to say, “No I’m not a prophet” they say “Yes you are, you’re a prophet.” I said, “No it’s not me.” They used to say “You sure are a prophet.” They used to convince me I was a prophet. Now I come out and say Jesus Christ is the answer. They say, “Bob Dylan’s no prophet.” They just can’t handle it.”

The album that followed Dylan’s conversion was the compelling Slow Train Coming. It won Dylan a Grammy for “Best Male Vocalist” for the song “Gotta Serve Somebody.” While the album sold well Dylan took a lot of heat in the press for his conversion. When he toured from the fall of 1979 to the spring of 1980 Dylan talked about his faith saying things like: “Years ago they … said I was a prophet. I used to say, “No I’m not a prophet” they say “Yes you are, you’re a prophet.” I said, “No it’s not me.” They used to say “You sure are a prophet.” They used to convince me I was a prophet. Now I come out and say Jesus Christ is the answer. They say, “Bob Dylan’s no prophet.” They just can’t handle it.”

And so it was. People didn’t mind other people embracing a particular faith but they got angry when Bob Dylan did it. Why? Because Dylan had long been established as the voice of truth. And when the voice of truth says you need Jesus you have to reckon with it. Many responded in anger. By the next album, Saved, in 1980, a lot of people seemed to be hopping mad about it. Dylan has never been afraid to go up against criticism and his records still sold, but after awhile, all but his truest fans weren’t listening to the songs or anything he had to say about his faith. They just couldn’t let it go.

Dylan sang on “We Are the World” the fundraising single for Africa’s famine relief and on July 13, 1985, he appeared at the climax of the Live Aid concert at JFK Stadium in Philadel-phia backed by Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood from the Rolling Stones. He sang a ragged version of “Hollis Brown”, his song about rural poverty, and then said to a worldwide audience of over one billion people: “I hope that some of the money … maybe they can just take a little bit of it, maybe … one or two million, maybe … and use it to pay the mortgages on some of the farms and, the farmers here, owe to the banks.” Naturally, his remarks were widely criticized as inappropriate, but they inspired Willie Nelson to organize Farm Aid to benefit debt-ridden American farmers.

In January 1988 Dylan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Bruce Springsteen declaring, “Bob freed your mind the way Elvis freed your body. He showed us that just because music was innately physical did not mean that it was anti-intellectual. In the fall of that same year Dyland co-founded the Traveling Wilburys with George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison, and Tom Petty. Their multi-platinum Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 reached number three on the US album chart and featured songs that were described as Dylan’s most accessible compositions in years. After Orbison’s died in December 1988, the remaining four recorded a second album. Dylan then released Oh Mercy which included “Most of the Time”, a song later prominently featured in the film High Fidelity and “What Was It You Wanted?” which most interpret as a wry comment on the expectations of critics and fans. Though he had backed off from the overtly Gospel songs the album included “Ring Them Bells”, a song about faith.

In fact, though Dylan told interviewers he had re-embraced his Jewish faith he never really has back off from his spirituality. Every album contains lyrics and themes that are virtually right out of the Bible. I don’t believe Bob gave up on Christianity. He just realized that he could be far more effective if he stopped challenging people head on with it.

In a 2004 interview with 60 Minutes he told Ed Bradley that “the only person you have to think twice about lying to is either yourself or to God.” He also explained his constant touring schedule as part of a bargain he made a long time ago with the “chief commander—in this earth and in the world we can’t see.” In a 2009 interview with Bill Flanagan promoting his Christmas in the Heart album, Flanagan commented on the “heroic performance” Dylan gave of “O Little Town of Bethlehem” and that Dylan “delivered the song like a true believer”. Dylan replied: “Well, I am a true believer.”

In 1991, Dylan was honored by a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award from the recording industry. The event coincided with the beginning of the Gulf War and Dylan performed his song “Masters of War” and then made a short speech that startled some of the audience:

In 1991, Dylan was honored by a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award from the recording industry. The event coincided with the beginning of the Gulf War and Dylan performed his song “Masters of War” and then made a short speech that startled some of the audience:

Well, my daddy, he didn’t leave me much – you know he was a very simple man, and he didn’t leave me a lot – but what he did tell me was this. He did say, son, he said…he said so many things, you know…. He say, you know it’s possible to become so defiled in this world that your own mother and father will abandon you, and if that happens, God will always believe in your own ability to mend your own ways.

Those who believed Dylan had stepped away from his beliefs began to wonder again.

In the next few years Dylan recorded Good as I Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993) which included “Lone Pilgrim” written by a teacher from the 19th century and sung with a haunting reverence. Dylan did an MTV Unplugged in November of 1994, but later that Spring was hospitalized with a life-threatening heart infection. He cancelled his European tour but soon left the hospital saying, “I really thought I’d be seeing Elvis soon.” By midsummer he was back on the road and in the fall performed before Pope John Paul II at the World Euch-aristic Conference in Bologna, Italy. The Pope then gave a sermon to the 200,000 people in the audience that was based on Dylan’s “Blowing in the Wind”.

In September of 1997, he released Time Out of Mind, his first collection of original songs in seven years which won him his first solo “Album of the Year” Grammy Award. In December 1997, President Bill Clinton honored Dylan in the East Room of the White House saying; “He probably had more impact on people of my generation than any other creative artist. His voice and lyrics haven’t always been easy on the ear, but throughout his career Bob Dylan has never aimed to please. He’s disturbed the peace and discomforted the powerful.”

When Time Magazine did their end of the century list of the “Most Important People of the Century, Bob Dylan was on it, described as a “master poet, caustic social critic and intrepid, guiding spirit of the counterculture generation”.

In March of 2001, Dylan won his first Oscar for his song “Things Have Changed” which he wrote for the film Wonder Boys. Since then he has often carried the award (or a facsimile of it) on the road with him, sitting it on top of an amplifier which he performs. On August 29, 2006, Dylan released Modern Times which entered the U.S. charts at number one, making it Dylan’s first album to reach that position since 1976’s Desire. Nominated for three Grammy Awards, Modern Times won Best Contemporary Folk/Americana Album and Dylan also won Best Solo Rock Vocal Performance for “Someday Baby”. Modern Times was named Album of the Year, for 2006, by Rolling Stone magazine

In 2007 a study of United States legal opinions determined that Dylan’s lyrics were quoted by judges and lawyers more than those of any other songwriter, 186 times versus 74 by The Beatles, who were second. Among those quoting Dylan were conservative Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Antonin Scalia, both conservatives. The most widely cited lines included “you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows” from “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “when you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose” from “Like a Rolling Stone”.

In 2007 a study of United States legal opinions determined that Dylan’s lyrics were quoted by judges and lawyers more than those of any other songwriter, 186 times versus 74 by The Beatles, who were second. Among those quoting Dylan were conservative Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Antonin Scalia, both conservatives. The most widely cited lines included “you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows” from “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “when you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose” from “Like a Rolling Stone”.

In 2008, the Pulitzer Prize jury awarded Bob Dylan a special citation for “his profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power.”

In 2009 Dylan released Together Through Life in April which contained songs he had written with long-time Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter It was his 33rd studio album and debuted at #1 on the American charts. In November of that same year he released Christmas in the Heart his first Christmas album. A collection of hymns, carols and popular Christmas songs, all royalties from the album went to benefit the charities Feeding America in the USA, Crisis in the UK, and the World Food Programme.

The “Never Ending Tour” commenced on June 7, 1988, and Dylan has played roughly 100 dates a year for the entirety of the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century—a heavier schedule than most performers who started out in the 1960s. By the end of 2010, Dylan and his band had played more than 2300 shows. Ever changing Dylan alters his arrangements and changes his vocal approach night after night.

Dylan’s performances in China in April 2011 generated controversy. Some criticized him for not commenting on the political situation in China, and for, allegedly, allowing the Chinese authorities to censor his set-list. Which Dylan denied saying on his website, “As far as censor-ship goes, the Chinese government had asked for the names of the songs that I would be playing. There’s no logical answer to that, so we sent them the set lists from the previous 3 months. If there were any songs, verses or lines censored, nobody ever told me about it and we played all the songs that we intended to play.”

Like many artists Dylan’s personal life has been up and down. He married Sara Lownds (the sad eyed lady of the lowlands) on November 22, 1965. Their first child, Jesse Byron Dylan, was born on January 6, 1966, and they had three more children: Anna Lea, Samuel Isaac Abraham, and Jakob Luke (born December 9, 1969). Dylan also adopted Sara’s daughter from a prior marriage, Maria Lownds (later Dylan, born October 21, 1961). In the 1990s Dylan’s son Jakob became well known as the lead singer of the Wallflowers. Jesse Dylan is a film director and a successful businessman. Bob and Sara Dylan were divorced on June 29, 1977. In June 1986, Dylan married his longtime backup singer Carolyn Dennis). Their daughter, Desiree Gabrielle Dennis-Dylan, was born on January 31, 1986. The couple divorced in October 1992.

A true renaissance man Dylan has been very involved in film and visual art as well as music. . In 1972, he wrote songs and backing music for Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garret & Billy the Kid and playing the role of “Alias,” a member of Billy’s gang with some historical basis. Despite the film’s failure at the box office, the song “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” has become one of Dylan’s most extensively covered songs. Dylan’s 1975 tour also provided the backdrop to his nearly four-hour film Renaldo and Clara, a wildly improvised mixture of concert footage and reminiscences. Released in 1978, the movie received awful and had a very brief theatrical run. Later in the year, a two-hour edit that mostly featured the concert footage had a much wider release. In 1987, Dylan starred in Richard Marquand’s Hearts of Fire, playing Billy Parker, a washed-up-rock-star-turned-chicken farmer whose teenage lover (played by Fiona) leaves him for an English pop sensation (played by Rupert Everett). Dylan contributed two original songs to the movie, “Night After Night”, and “I Had a Dream About You, Baby”, as well as a cover of John Hiatt’s “The Usual”, but the film was not well received by cricits or the public

A true renaissance man Dylan has been very involved in film and visual art as well as music. . In 1972, he wrote songs and backing music for Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garret & Billy the Kid and playing the role of “Alias,” a member of Billy’s gang with some historical basis. Despite the film’s failure at the box office, the song “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” has become one of Dylan’s most extensively covered songs. Dylan’s 1975 tour also provided the backdrop to his nearly four-hour film Renaldo and Clara, a wildly improvised mixture of concert footage and reminiscences. Released in 1978, the movie received awful and had a very brief theatrical run. Later in the year, a two-hour edit that mostly featured the concert footage had a much wider release. In 1987, Dylan starred in Richard Marquand’s Hearts of Fire, playing Billy Parker, a washed-up-rock-star-turned-chicken farmer whose teenage lover (played by Fiona) leaves him for an English pop sensation (played by Rupert Everett). Dylan contributed two original songs to the movie, “Night After Night”, and “I Had a Dream About You, Baby”, as well as a cover of John Hiatt’s “The Usual”, but the film was not well received by cricits or the public

A longtime visual artist Dylan has published three books of drawings and paintings beginning with Drawn Blank (1994) and his work has been exhibited in major art galleries. The Drawn Blank Series, opened in October 2007 at the Kunstsammlungen in Chemnitz, Germany which showcased more than 200 watercolors. From September 2010 until April 2011, the National Gallery of Denmark exhibited 40 large-scale acrylic paintings by Dylan entitled, The Brazil Series.

On May 29, 2012, U.S. President Barack Obama awarded Dylan a Presidential Medal of Freedom in the White House. At the ceremony, Obama praised Dylan’s voice for its “unique gravelly power that redefined not just what music sounded like but the message it carried and how it made people feel”.

On September 11, 2012, Dylan released his 35th studio album, Tempest. The album features a tribute to John Lennon, “Roll On John”, and the title track is a 14 minute song about the sinking of the Titanic. Reviewing Tempest for Rolling Stone, Will Hermes gave the album five out of five stars, writing: “Lyrically, Dylan is at the top of his game, joking around, dropping wordplay and allegories that evade pat readings and quoting other folks’ words like a freestyle rapper on fire.” Hermes called Tempest “one of [Dylan’s] weirdest albums ever”, and opined, “It may also be the single darkest record in Dylan’s catalog.” The critical aggregator website Metacritic awarded the album a score of 83 out of 100, indicating “universal acclaim”.

On August 27, 2013, Columbia Records released Volume 10 of Dylan’s Bootleg Series, Another Self Portrait (1969–1971). The album contained 35 previously unreleased tracks, including alternate takes and demos from Dylan’s 1969–1971 recording sessions during the making of the Self Portrait and New Morning albums. The box set also included a live recording of Dylan’s performance with the Band at the Isle of Wight Festival in 1969. Another Self Portrait received favorable reviews, earning a score of 81 on the critical aggregator, Metacritic, indicating “universal acclaim”.[310] AllMusic critic Thom Jurek wrote, “For fans, this is more than a curiosity, it’s an indispensable addition to the catalog.”

On November 4, 2013, Columbia Records released Bob Dylan: Complete Album Collection: Vol. One, a boxed set containing all 35 of Dylan’s studio albums, six albums of live recordings, and a collection, entitled Sidetracks, of singles, songs from films and non-album material.[312] The box includes new album-by-album liner notes written by Clinton Heylin with an introduction by Bill Flanagan.

On the same date, Columbia released a compilation, The Very Best of Bob Dylan, which is available in both single CD and double CD formats. To publicize the 35 album box set, an innovative video of the song “Like a Rolling Stone” was released on Dylan’s website. The interactive video, created by director Vania Heymann, allowed viewers to switch between 16 simulated TV channels, all featuring characters who are lip-synching the lyrics of the 48-year-old song.[314][315]

On February 2, 2014, Dylan appeared in a commercial for the Chrysler 200 car which was screened during the 2014 Super Bowl American football game. At the end of the commercial, Dylan says: “So let Germany brew your beer, let Switzerland make your watch, let Asia assemble your phone. We will build your car.” Dylan’s Super Bowl commercial generated controversy and op-ed pieces discussing the protectionist implications of his words, and whether the singer had “sold out” to corporate interests.

On February 2, 2014, Dylan appeared in a commercial for the Chrysler 200 car which was screened during the 2014 Super Bowl American football game. At the end of the commercial, Dylan says: “So let Germany brew your beer, let Switzerland make your watch, let Asia assemble your phone. We will build your car.” Dylan’s Super Bowl commercial generated controversy and op-ed pieces discussing the protectionist implications of his words, and whether the singer had “sold out” to corporate interests.

In 2013 and 2014, auction house sales demonstrated the high cultural value attached to Dylan’s mid-1960s work, and the record prices that collectors were willing to pay for artefacts from this period. In December 2013, the Fender Stratocaster which Dylan had played at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival fetched $965,000, the second highest price paid for a guitar. In June 2014, Dylan’s hand-written lyrics of “Like a Rolling Stone”, his 1965 hit single, fetched $2 million dollars at auction, a record for a popular music manuscript.

On October 28, 2014, Simon & Schuster published a massive 960 page, thirteen and a half pound edition of Dylan’s lyrics, The Lyrics: Since 1962. The book was edited by literary critic Christopher Ricks, Julie Nemrow and Lisa Nemrow, to offer variant versions of Dylan’s songs, sourced from out-takes and live performances. A limited edition of 50 books, signed by Dylan, was priced at $5,000. “It’s the biggest, most expensive book we’ve ever published, as far as I know,” said Jonathan Karp, Simon & Schuster’s president and publisher.

On November 4, 2014, Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings released The Basement Tapes Complete by Bob Dylan and the Band. These 138 tracks in a six-CD box form Volume 11 of Dylan’s Bootleg Series. The 1975 album, The Basement Tapes, contained some of the songs which Dylan and the Band recorded in their homes in Woodstock, New York, in 1967. Subsequently, over 100 recordings and alternate takes have circulated on bootleg records. The sleeve notes for the new box set are by Sid Griffin, American musician and author of Million Dollar Bash: Bob Dylan, the Band, and the Basement Tapes.

On February 3, 2015, Dylan released Shadows in the Night, featuring ten songs written between 1923 and 1963, which have been described as part of the Great American Songbook. All the songs on the album were recorded by Frank Sinatra but both critics and Dylan himself cautioned against seeing the record as a collection of “Sinatra covers”. Dylan explained, “I don’t see myself as covering these songs in any way. They’ve been covered enough. Buried, as a matter a fact. What me and my band are basically doing is uncovering them. Lifting them out of the grave and bringing them into the light of day.” In an interview, Dylan said he had been thinking about making this record since hearing Willie Nelson’s 1978 album Stardust favorable reviews, scoring 82 on the critical aggregator Metacritic, which indicates “universal acclaim”. Critics praised the restrained instrumental backings and Dylan’s singing, saying that the material had elicited his best vocal performances in recent years. Bill Prince in GQ commented: “A performer who’s had to hear his influence in virtually every white pop recording made since he debuted his own self-titled album back in 1962 imagines himself into the songs of his pre-rock’n’roll early youth.” In The Independent, Andy Gill wrote that the recordings “have a lingering, languid charm, which… help to liberate the material from the rusting manacles of big-band and cabaret mannerisms.” The album debuted at number one in the UK Albums Chart in its first week of release.

On October 5, 2015, IBM launched a marketing campaign for its Watson computer system which featured Dylan. Dylan is seen conversing with the computer which says it has read all his lyrics and reports: “My analysis shows that your major themes are that time passes and love fades.” Dylan replies: “That sounds about right.”

On November 6, 2015, Sony Music released The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965–1966. This work consists of previously unreleased material from the three albums Dylan recorded between January 1965 and March 1966: Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. The records have been released in three formats: a 2-CD “Best Of” version, a 6-CD “Deluxe edition”, and an 18-CD “Collector’s Edition” in a limited edition of 5,000 units. On Dylan’s website the “Collector’s Edition” was described as containing “every single note recorded by Bob Dylan in the studio in 1965/1966”. The critical aggregator website Metacritic awarded Cutting Edge a score of 99, indicating universal acclaim. The Best of the Cutting Edge entered the Billboard Top Rock Albums chart at number one on November 18, based on its first-week sales.

On March 2, 2016, it was announced that Dylan had sold an extensive archive of about 6,000 items to the George Kaiser Family Foundation and the University of Tulsa. It was reported that the sale price was “an estimated $15 million to $20 million”, and the archive comprises notebooks, drafts of Dylan lyrics, recordings, and correspondence. Filmed material in the collection includes 30 hours of outtakes from the 1965 tour documentary Dont Look Back, 30 hours of footage shot on Dylan’s legendary 1966 electric tour, and 50 hours shot on the 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue. The archive will be housed at Helmerich Center for American Research, a facility at the Gilcrease Museum.

On May 20, Dylan released Fallen Angels, which was described as “a direct continuation of the work of ‘uncovering’ the Great Songbook that he began on last year’s Shadows In the Night.” The album contained twelve songs by classic songwriters such as Harold Arlen, Sammy Cahn and Johnny Mercer, eleven of which had been recorded by Sinatra. Jim Farber wrote in Entertainment Weekly: “Tellingly, [Dylan] delivers these songs of love lost and cherished not with a burning passion but with the wistfulness of experience. They’re memory songs now, intoned with a present sense of commitment. Released just four days ahead of his 75th birthday, they couldn’t be more age-appropriate.” The album received a score of 79 on critical aggregator website Metacritic, denoting “generally favorable reviews”.

On October 13, the Nobel Prize committee announced it had awarded Dylan the Nobel Prize in Literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”.

On November 11, 2016, Legacy Recordings released a 36-CD set, Bob Dylan: The 1966 Live Recordings, including every known recording of Bob Dylan’s 1966 concert tour. Legacy Recordings president Adam Block said: “While doing the archival research for The Cutting Edge 1965–1966, last year’s box set of Dylan’s mid-’60s studio sessions, we were continually struck by how great his 1966 live recordings really are.” The recordings commence with the concert in White Plains New York on February 5, 1966, and end with the Royal Albert Hall concert in London on May 27. The liner notes for the set are by Clinton Heylin, author of the book, Judas!: From Forest Hills to the Free Trade Hall: A Historical View of Dylan’s Big Boo, a study of the 1966 tour. The New York Times reported most of the concerts had “never been heard in any form”, and described the set as “a monumental addition to the corpus”.

On March 31, 2017, Dylan released his triple album, Triplicate. The three albums comprise 30 new recordings of classic American songs, including “As Time Goes By” by Herman Hupfeld and “Stormy Weather” by Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler. The album was recorded in Hollywood’s Capitol Studios and features Dylan’s touring band. Triplicate is Dylan’s 38th studio album. Dylan posted a long interview on his website to promote the album, and was asked if this material was an exercise in nostalgia. “Nostalgic? No I wouldn’t say that. It’s not taking a trip down memory lane or longing and yearning for the good old days or fond memories of what’s no more. A song like “Sentimental Journey” is not a way back when song, it doesn’t emulate the past, it’s attainable and down to earth, it’s in the here and now.” The album was awarded a score of 84 on critical aggregator website Metacritic, signifying “universal acclaim”. Critics praised the thoroughness of Dylan’s exploration of the great American songbook, though, in the opinion of Uncut: “For all its easy charms, Triplicate labours its point to the brink of overkill. After five albums’ worth of croon toons, this feels like a fat full stop on a fascinating chapter.”

Bob Dylan has released 75 albums, one for every year he’s been alive.

So what happened with Bob and I going to see Hal Lindsey and maybe developing a movie together? Nothing. I called several times, but Bob never returned my call. But there was a larger, spiritual truth that I learned from the experience. Seek the kingdom first and all else will be added unto you. That’s a bible verse that means if we seek God first, He will take care of everything else. I had moved from Kankakee to Malibu and I was a hot shot writer. I kept feeling God was leading me to find a church so I could continue to grow spiritually in the direction He wanted me to grow in but I was so busy trying to get my career happing and dealing with the fact that my rent had gone from $145 a month in Kankakee to $1050 a month in Malibu. Then, finally I decided I’d better put God as my top priority and I went to church. He then showed me in the most dynamic way possible that if would seek Him first, he could make the rest happen. Including suddenly connecting with one of my idols and having the opportunity to work with him. Even though it didn’t work out I never forgot that lesson and keeping those priorities straight has served me well in dealing with some of the biggest names in Hollywood throughout my career. And, as for Bob, I never resented him for not getting back to me. I think I understand about that. I mean he’s Bob Dylan. It’s not easy being Bob.

___

No Comment