Four Republican Candidates and Their Four Big Myths: Paula Dwyer

©2016 Bloomberg View

O3TUY46KLVRD

(Bloomberg View) — In Donald Trump’s telling, Mexico, Japan and especially China are fleecing the U.S. because past presidents were inept negotiators and too timid to muscle America’s trading partners.

But even if a President Trump could stop companies from offshoring or countries from manipulating currencies — possibly by strong-arming Congress into imposing 35 percent tariffs on imports — those jobs aren’t coming back. This is the big myth propelling Trump’s surprisingly successful candidacy.

Trump can’t do what he claims for many reasons, including that the U.S. manufacturing slide began well before China’s ascent. Most jobs that moved to China, Mexico and other cheap- labor locales have already been replaced by automation. The foreign workers who once made toys, electronics and clothing for the American consumer have themselves been displaced: Manufacturing jobs are in decline not only in China but all over the world.

What’s more, companies that return to the U.S. — to take advantage of tax breaks and falling natural-gas prices or to protect intellectual property, for example — hire a fraction of the workers that old-line manufacturers once employed. If Trump made the penalties so big that companies never left, the inability to compete against overseas rivals with lower labor costs eventually would lead to more automation and layoffs at home.

While Trump is often criticized for simplistic sloganeering, Ted Cruz may be selling the biggest myth of all: That a return to the gold standard would prevent inflation and make the U.S. economy flush again. No country today uses the gold standard, for good reason.

Backing dollars with the precious metal — meaning anyone could walk into a bank and demand conversion of dollars to gold — is a theory that sits far outside mainstream thought. In a survey of economists with a wide range of political views, not one advocated a return to a gold standard.

In theory, the limits in the supply of gold would mean banks couldn’t expand the money supply by lending more than their gold stockpiles allowed. But throughout history, gold- backed currencies crimped growth by making it hard to get credit to start or expand a business or buy a home. The gold standard also led to frequent crises when panicked depositors demanded gold in place of money, causing banks to fail and recessions to erupt.

Conservatives may like that a gold standard would deny Congress the ability to finance wars or stimulate a shrinking economy with deficit spending. But it would also deny the Federal Reserve the ability to manage the economy by lowering interest rates and loosening credit when it’s most needed. What’s more, if the U.S. ran a trade deficit with another country, the Fed would have to raise interest rates to lure gold back to the U.S., risking deflation, recession or both.

John Kasich’s obsession with balanced budgets is just as economically misguided as Cruz’s is with gold. A former House Budget Committee chairman, Kasich calls for a balanced-budget amendment to the Constitution.

It sounds like a common-sense idea to many voters since it’s true Congress has been negligent in managing the federal budget. Yet there is currently no budget crisis. This fiscal year’s projected deficit of $544 billion, at 2.9 percent of gross domestic product, is within the range of what budget experts consider sustainable. As baby-boomer retirements increase, deficits will grow, but Congress has plenty of time to figure out how to control them. More important, the U.S. Treasury is having no problem selling bonds, with interest rates still at rock bottom.

A deficit-free economy would require perpetual austerity, even in times of contraction, when more government spending and tax cuts help boost demand and avoid mass unemployment. A balanced-budget diktat would have made the 2008-2009 financial crisis harder to control; the $880 billion stimulus law would have been unthinkable.

Some Republicans (who tend to favor balanced budgets until they prevent tax cuts) and budget hawks (who tend to worry the U.S.’s debt load crowds out private investment) oppose tying the government’s hands by amending the Constitution. Even Ronald Reagan, who campaigned on the balanced-budget amendment idea, never really tried to make it happen.

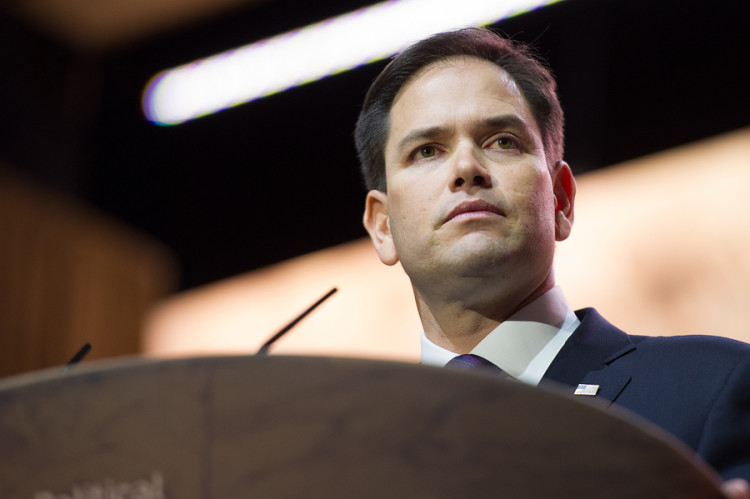

Of the four candidates remaining in the Republican race, none has been as passionate as Marco Rubio in emphasizing the need to address inequality by strengthening middle-class families. He would do this mainly with a new tax credit of up to $2,500 a child. It would be in addition to an existing $1,000- per-child tax credit and could offset other levies, including Social Security taxes.

It would certainly help middle-income families with multiple kids. (The credit begins to phase out when household income exceeds $300,000.)

Yet Rubio’s proposed tax plan, a type of value-added tax, would do much more to help rich Americans. Overall, he would cut taxes nearly twice as much as George W. Bush did, and high- income taxpayers would receive the largest benefit in dollars and percentage terms.

A study by a middle-of-the-road think tank, the Tax Policy Center, said the top 0.1 percent of taxpayers (with incomes exceeding $3.8 million) would see an average tax cut of about $930,000, representing 13.6 percent of their after-tax income. Households in the middle fifth of the income distribution (making up to $80,760) would get a $1,400 tax cut, or 2.5 percent of after-tax income. The poorest 20 percent of households (incomes up to $23,099) would see their taxes go down by about $250, raising after-tax incomes by 1.9 percent.

Perhaps the most outlandish idea in Rubio’s plan would eliminate taxes on investment income. That would allow, say, Warren Buffett to pay little or no tax because, like most wealthy people, most of his income comes not from a salary but from gains on the sale of property and other assets, stock dividends and interest payments.

That’s the opposite of pro-middle-class. Unless you believe in myths.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story: Paula Dwyer at pdwyer11@bloomberg.net To contact the editor responsible for this story: Katy Roberts at kroberts29@bloomberg.net

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit http://www.bloomberg.com/view

No Comment