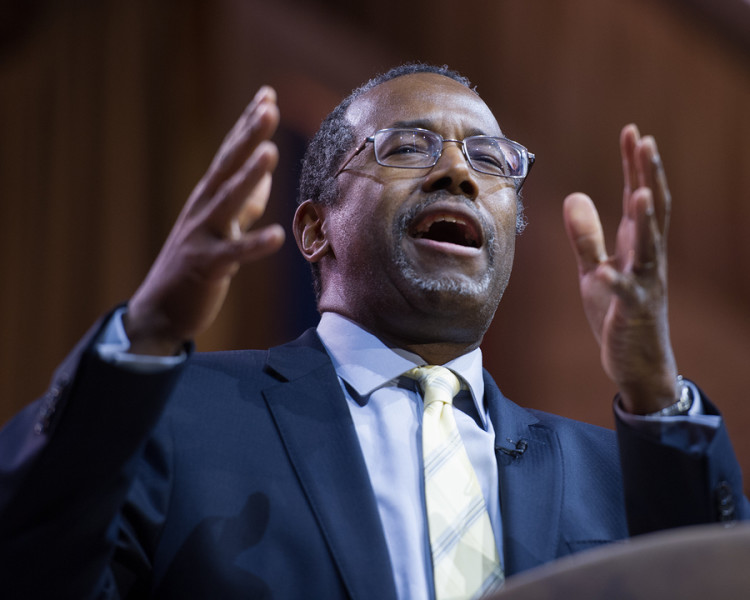

Ben Carson’s Character Is His 2016 Campaign: Francis Wilkinson

©2015 Bloomberg View

NXKJ2B6JTSED

(Bloomberg View) — In the race for the Republican nomination for president, Ben Carson and Donald Trump are basically co-leaders in the polls. For now, they dominate the Republican field.

Carson is running an “outsider” campaign, has no significant experience in politics or government and reveals little interest in, or understanding of, large swaths of public policy. Trump is running similarly, with a nearly identical lack of experience or obvious interest in governing. Carson has said some things in books and elsewhere that appear to be misremembered, or possibly untrue. Trump has said some things in books and elsewhere that likewise appear untrue.

In the end, Carson could lose support if his personal narrative proves untrustworthy. Trump? If he falters, it probably won’t be due to re-evaluations of his character.

The divergence reveals how fundamentally different their campaigns are, despite surface similarities. Trump is running as a mechanical genius who can fix all manner of stuff — borders, trade agreements, manufacturing base, national debt. Carson is running as a redeemer who can restore American Eden, paving the way for Christian righteousness to reign throughout the land. Neither claim is remotely plausible. But unlike Trump’s calling card, which emphasizes his skills rather than his heart, Carson’s claim is utterly dependent on the content of his character. If that content becomes suspect, the rationale for his candidacy erodes.

As Kevin Drum and others have pointed out, Carson’s public biography is itself a redemption tale. A wayward youth facing all the dead ends of poverty, racial disadvantage and inner-city dysfunction is consumed with anger until he acts on his rage, stabbing a friend (or a relative, in Carson’s most recent telling) and has a spiritual epiphany. Carson is saved — preserved for a greater destiny — by the grace of God. In another Carson story, he is put in a situation at college that reveals his incorruptibility to a professor. As a consequence, Carson receives a small financial reward at an hour of maximum need. No matter the adversity, the Dude abides.

Carson’s description of a God that is not only immanent but interventionist no doubt resonates with some Christian conservatives. (I once overheard a young woman in the parking lot of Pat Robertson’s Regent University in Virginia tell a friend that God had told her to turn left when she was driving in search of a particular store.)

Trump, on the other hand, has little to offer voters looking for a candidate with a history of divine guidance. Indeed, Trump’s efforts to portray himself as steeped in the Bible and Christian belief are among the most transparent of an often brazen campaign, even inspiring a TrumpBible Twitter account.

Trump can afford a flawed character. He can use cunning, and fudge at the margins, provided he brings the trophy home in the end. Carson is supposed to win, too. But he has to do so while being a model of sportsmanship and superior virtue.

That’s a tall order in politics at any level, but especially the presidential arena. In this instance, rival campaigns and the news media are working to achieve similar, if separate, ends — greater scrutiny and exposure of Carson – and he is now on the defensive.

“My prediction is that all of you guys trying to pile on is actually going to help me,” Carson said to reporters at a news conference last weekend. Under attack, Carson has shown flashes of self-pity along with a conspiratorial bent.

That isn’t unique, as students of the Bill Clinton White House can confirm. In the 2016 race, Trump has been quick to whine and blame others. And the “liberal media” is the target of first resort for Republican candidates who don’t like the questions they’ve been asked. Carson is probably right that blaming the press will help him shore up voter support in the short run.

Still, personal virtue is a fragile foundation for a presidential campaign and Eden makes for a difficult platform. If Carson’s religious narratives turn out to look more like contingency than destiny, his support will likely crumble. Having established a claim to sacred space, Carson can’t be seen sharing it with Mammon.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story: Francis Wilkinson at fwilkinson1@bloomberg.net To contact the editor responsible for this story: Katy Roberts at kroberts29@bloomberg.net

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit http://www.bloomberg.com/view

No Comment