A Well Thought Out Scream By James Riordan: New Horizons Explores Pluto – The Oddball Planet

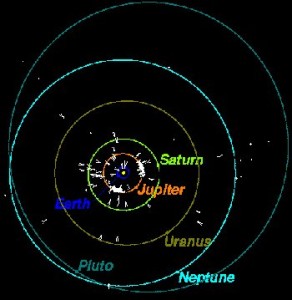

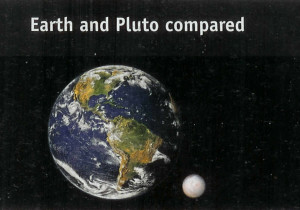

It’s orbit is wildly out of whack compared to the eight official planets in our solar system. It is nearly twice as far as the next closest planet. And, essentially, it’s just a big ball of ice. Well, actually, in astronomical terms, it’s a little ball of ice, only one sixth the mass of our moon and only one third of its volume. Pluto has the most eccentric orbit of all the planets in the solar system. Its orbit takes it to 49.5 AU (7.4 billion kilometers) at its farthest point from the Sun. And its orbit takes it as close as 29 AU (4.34 billion kilometers) to the Sun. That means that Pluto’s orbit draws within the orbit of Neptune, as can be seen in the drawing below, making Pluto the 8th planet rather than the 9th planet for roughly 20 years at a time. Pluto was the 8th planet from January 1979 to February 1999. Neptune is now the 9th planet for over 200 years! It takes 248 years for Pluto to complete its orbit. This means that a single Pluto year is 248 earth years long.

Pluto has five known moons: Charon (the largest, with a diameter just over half that of Pluto), Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. Pluto and Charon are sometimes considered a binary system because the barycenter of their orbits does not lie within either body. The IAU has not formalized a definition for binary dwarf planets, and Charon is officially classified as a moon of Pluto.

Pluto has five known moons: Charon (the largest, with a diameter just over half that of Pluto), Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. Pluto and Charon are sometimes considered a binary system because the barycenter of their orbits does not lie within either body. The IAU has not formalized a definition for binary dwarf planets, and Charon is officially classified as a moon of Pluto.

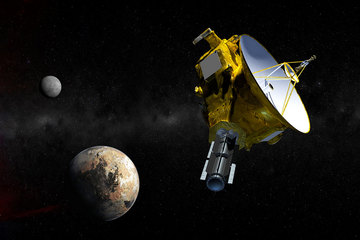

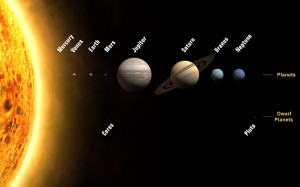

Pluto was discovered in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh, and was originally considered the ninth planet from the Sun. After 1992, its status as a planet fell into question following the discovery of several objects of similar size in the Kuiper belt. Now it is considered a dwarf planet. We never can see it with just our naked eye. It took the New Horizons spacecraft, traveling at 58,536 kilometers per hour (36,373 miles per hour) nine and a half years to reach it. The New Horizons spacecraft was the fastest ship ever built leaving earth’s orbit at or a hundred times faster than a jetliner.

Pluto was discovered in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh, and was originally considered the ninth planet from the Sun. After 1992, its status as a planet fell into question following the discovery of several objects of similar size in the Kuiper belt. Now it is considered a dwarf planet. We never can see it with just our naked eye. It took the New Horizons spacecraft, traveling at 58,536 kilometers per hour (36,373 miles per hour) nine and a half years to reach it. The New Horizons spacecraft was the fastest ship ever built leaving earth’s orbit at or a hundred times faster than a jetliner.

New Horizons was launched as part of NASA’s New Frontiers program. Engineered by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and the Southwest Research Institute, with a team led by S. Alan Stern, the spacecraft was launched to study Pluto, its moons and the Kuiper belt, performing flybys of the Pluto system and one or more other Kuiper belt objects. The program was the result of many years of work on missions to send a spacecraft to Pluto, starting in 1990 with Pluto 350, with Alan Stern and Fran Bagenal of the “Pluto Underground”, and in 1992 with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Pluto Fast Flyby; the latter inspired by a United States Postal Service stamp that branded Pluto as “Not Yet Explored”. The ambitious mission aimed to send a lightweight, cost-effective spacecraft to Pluto, later evolving into a Kuiper belt object mission named Pluto Kuiper Express. However, because of underwhelming support from NASA and growing projected cost, the project was eventually cancelled altogether in 2000. Following backlash from the cancellation, the New Frontiers program was established for missions that fit in between the big budgets of the Flagship Program and the low budgets of the Discovery Program. The Applied Physics Laboratory, with a team consisting of former Pluto Kuiper Express team members, won a competition to fund their New Horizons project, based on work left off from Pluto Kuiper Express, under the New Frontiers program. However, funding for the mission was not secured until after a financial standoff between the team and then-NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe. After three years of construction, and several delays at the launch site, New Horizons was launched on January 19, 2006, from Cape Canaveral. After a brief encounter with asteroid 132524 APL, New Horizons proceeded to Jupiter, making its closest approach on February 28, 2007, at a distance of 2.3 million kilometers (1.4 million miles). The Jupiter flyby provided a gravity assist that increased New Horizons ’ speed by 4 km/s (14,000 km/h; 9,000 mph). The encounter was also used as a general test of New Horizons ’ scientific capabilities, returning data about the planet’s atmosphere, moons, and magnetosphere.

New Horizons was launched as part of NASA’s New Frontiers program. Engineered by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and the Southwest Research Institute, with a team led by S. Alan Stern, the spacecraft was launched to study Pluto, its moons and the Kuiper belt, performing flybys of the Pluto system and one or more other Kuiper belt objects. The program was the result of many years of work on missions to send a spacecraft to Pluto, starting in 1990 with Pluto 350, with Alan Stern and Fran Bagenal of the “Pluto Underground”, and in 1992 with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Pluto Fast Flyby; the latter inspired by a United States Postal Service stamp that branded Pluto as “Not Yet Explored”. The ambitious mission aimed to send a lightweight, cost-effective spacecraft to Pluto, later evolving into a Kuiper belt object mission named Pluto Kuiper Express. However, because of underwhelming support from NASA and growing projected cost, the project was eventually cancelled altogether in 2000. Following backlash from the cancellation, the New Frontiers program was established for missions that fit in between the big budgets of the Flagship Program and the low budgets of the Discovery Program. The Applied Physics Laboratory, with a team consisting of former Pluto Kuiper Express team members, won a competition to fund their New Horizons project, based on work left off from Pluto Kuiper Express, under the New Frontiers program. However, funding for the mission was not secured until after a financial standoff between the team and then-NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe. After three years of construction, and several delays at the launch site, New Horizons was launched on January 19, 2006, from Cape Canaveral. After a brief encounter with asteroid 132524 APL, New Horizons proceeded to Jupiter, making its closest approach on February 28, 2007, at a distance of 2.3 million kilometers (1.4 million miles). The Jupiter flyby provided a gravity assist that increased New Horizons ’ speed by 4 km/s (14,000 km/h; 9,000 mph). The encounter was also used as a general test of New Horizons ’ scientific capabilities, returning data about the planet’s atmosphere, moons, and magnetosphere.

Most of the post-Jupiter voyage was spent in hibernation mode to preserve on-board systems, except for brief annual checkouts.[6] On December 6, 2014, New Horizons was brought back online for the Pluto encounter, and instrument check-out began. On January 15, 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft began its approach phase to Pluto. On July 14, 2015, it flew 12,500 km (7,800 mi) above the surface of Pluto, making it the first spacecraft to explore the dwarf planet. Thirteen hours later, NASA received the first communication from the probe following a flyby at the time expected. Engineering data indicated that the flyby was successful and the probe operated in all respects as expected.

Most of the post-Jupiter voyage was spent in hibernation mode to preserve on-board systems, except for brief annual checkouts.[6] On December 6, 2014, New Horizons was brought back online for the Pluto encounter, and instrument check-out began. On January 15, 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft began its approach phase to Pluto. On July 14, 2015, it flew 12,500 km (7,800 mi) above the surface of Pluto, making it the first spacecraft to explore the dwarf planet. Thirteen hours later, NASA received the first communication from the probe following a flyby at the time expected. Engineering data indicated that the flyby was successful and the probe operated in all respects as expected.

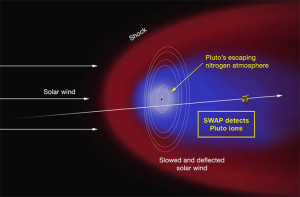

One of the oddities of Pluto that was confirmed by the mission was that the planet has an extended atmosphere, a long plasma tail reminiscent of a comet’s ion tail extending from the dwarf planet. While Pluto is 40 times further away from the sun than Earth, it is still influenced by the solar wind — a stream of ionized particles spiraling away from the sun. As the solar wind interacts with Pluto, it appears that the small world’s tenuous atmosphere is “blown back,” and lost to space, forming a long tail between 48,000 miles (77,000 km) and 68,000 miles (109,000 km) long. The New Horizon’s Mission suggests that Pluto’s predominantly nitrogen atmosphere is being ionized by ultraviolet light from the sun and then the ions are “picked up” by the solar wind, creating the long tail.

Artist’s concept of the interaction of the solar wind

Artist’s concept of the interaction of the solar wind

(the supersonic outflow of electrically charged particles

from the sun) with Pluto’s predominantly nitrogen atmosphere.

Credit : NASA/JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY APPLIED

PHYSICS LABORATORY/SOUTHWEST RESEARCH INSTITUTE

“This is just a first tantalizing look at Pluto’s plasma environment,” said Fran Bagenal, of the University of Colorado, Boulder, who leads the New Horizons Particles and Plasma team. “We’ll be getting more data in August, which we can combine with the Alice and Rex atmospheric measurements to pin down the rate at which Pluto is losing its atmosphere. Once we know that, we’ll be able to answer outstanding questions about the evolution of Pluto’s atmosphere and surface and determine to what extent Pluto’s solar wind interaction is like that of Mars.”

No Comment