Gang Violence in Mexico Driving New Wave of Illegal Immigrants : A Well Thought Out Scream by James Riordan

Most people are unaware of the vast gang netherworld. They thing of movies like The Blackboard Jungle or The Warriors, but have no real idea of todays armies of the night. I use that phrase because the film The Warriors was actually based on the novel Armies of the Night. There have been other great books detailing gang life like David Wilkerson’s classic, The Cross and the Switchblade which described Wilkerson’s brave jouney into the world of New York City gangs and the eventual conversion of gang leader Nicky Cruz. There is also Run Baby Run, written by Cruz himself. People think about the old gangs like L.A.’s Crypts and Bloods and Chicago’s Blackstone Nation. Motorcycle gangs like the Hell’s Angels and the Outlaws conjure up another image. The more recent gangs like the Gangster Disciples, the Vice Lords, the Latin Kings and the Harrison Gents have created much terror and heartache. There are literally hundreds more, but perhaps the mort notorious and deadly gang of today is called MS-13. The MS stands for Mara Salvatrucha. Some sources say the gang is named for La Mara, a street gang in San Salvador, and the Salvatrucha guerrillas who fought in the Salvadoran Civil War. Additionally, the word mara means gang in Caliche slang and is taken from marabunta, the name of a fierce type of ant. “Salvatrucha” may be a combination of the words Salvadoran and trucha, a Caliche word for being alert. The term “Salvatruchas” has been explained as a reference to Salvadorian peasants trained to become guerrilla fighters, referred to as the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front. The 13 represents their affiliation with the Sureño gang family is affiliated with the Mexican Mafia while in U.S. state and federal correctional facilities. Many Sureño gangs have rivalries with one another, and the only time this rivalry is set aside is when they enter the prison system.

Most people are unaware of the vast gang netherworld. They thing of movies like The Blackboard Jungle or The Warriors, but have no real idea of todays armies of the night. I use that phrase because the film The Warriors was actually based on the novel Armies of the Night. There have been other great books detailing gang life like David Wilkerson’s classic, The Cross and the Switchblade which described Wilkerson’s brave jouney into the world of New York City gangs and the eventual conversion of gang leader Nicky Cruz. There is also Run Baby Run, written by Cruz himself. People think about the old gangs like L.A.’s Crypts and Bloods and Chicago’s Blackstone Nation. Motorcycle gangs like the Hell’s Angels and the Outlaws conjure up another image. The more recent gangs like the Gangster Disciples, the Vice Lords, the Latin Kings and the Harrison Gents have created much terror and heartache. There are literally hundreds more, but perhaps the mort notorious and deadly gang of today is called MS-13. The MS stands for Mara Salvatrucha. Some sources say the gang is named for La Mara, a street gang in San Salvador, and the Salvatrucha guerrillas who fought in the Salvadoran Civil War. Additionally, the word mara means gang in Caliche slang and is taken from marabunta, the name of a fierce type of ant. “Salvatrucha” may be a combination of the words Salvadoran and trucha, a Caliche word for being alert. The term “Salvatruchas” has been explained as a reference to Salvadorian peasants trained to become guerrilla fighters, referred to as the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front. The 13 represents their affiliation with the Sureño gang family is affiliated with the Mexican Mafia while in U.S. state and federal correctional facilities. Many Sureño gangs have rivalries with one another, and the only time this rivalry is set aside is when they enter the prison system.

Members of MS are often covered in tattoos, including the face, and even have their own sign language. They are notorious for their violence and a subcultural moral code based on merciless retribution. Both the FBI and Immigration and Customs Enforcement have initiated wide-scale raids against known and suspected gang members, arresting hundreds across the United States.

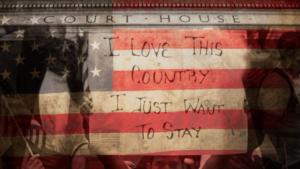

The MS-13 gang made Jose Osmin Aparicio’s life so miserable in his native El Salvador that he had no choice but to flee in the dead of night with his wife and four children, leaving behind all their belongings and paying a smuggler $8,000.

Aparicio is undeterred by a new directive from Attorney General Jeff Sessions declaring that gang and domestic violence will generally cease to be grounds for asylum. To him, it’s better to take his chances with the American asylum system and stay in Mexico if his bid is denied.

“Imagine what would happen if I was deported to El Salvador,” he said Wednesday as he waited at the border to enter the U.S.

Rubilia Sanchez knew she had to flee her hometown of Tecun Uman after gangs repeatedly threatened to rape and murder her. So she took her four daughters and made the familiar, dangerous trek out of Guatemala, through Mexico and into the United States, where she requested asylum. After waiting for four years, she finally got a date to plead her case to U.S. officials: July 26. But now, her already hazy future – and that of others fleeing gang violence in Latin America – has been thrust into greater uncertainty.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions ordered immigration judges to stop granting asylum to virtually all those claiming to be victims of domestic or gang violence, a move that could block tens of thousands of people from gaining permanent entry into the U.S.

The directive announced Monday could have far-reaching consequences because of the sheer volume of people like Aparicio fleeing gang violence, which is so pervasive in Central America that merely stepping foot in the wrong neighborhood can lead to death.

The Associated Press interviewed several asylum-seekers this past week at a plaza on the border, and each of them cited gang violence as the main factor in fleeing their homelands. They planned to press on with their asylum requests in spite of the new rule.

The decision by Sessions came as the administration faced a growing backlash over immigration policies and practices that human-rights advocates view as inhumane, including separating children from immigrant parents. They leveled similar criticism over the asylum changes, which the White House says are necessary to deter illegal immigration. “The mere fact that a country may have problems effectively policing certain crimes — such as domestic violence or gang violence — or that certain populations are more likely to be victims of crime, cannot itself establish an asylum claim,” the attorney general wrote Monday, overruling a Board of Immigration Appeals decision granting asylum to a Salvadoran woman fleeing her husband.

The decision by Sessions came as the administration faced a growing backlash over immigration policies and practices that human-rights advocates view as inhumane, including separating children from immigrant parents. They leveled similar criticism over the asylum changes, which the White House says are necessary to deter illegal immigration. “The mere fact that a country may have problems effectively policing certain crimes — such as domestic violence or gang violence — or that certain populations are more likely to be victims of crime, cannot itself establish an asylum claim,” the attorney general wrote Monday, overruling a Board of Immigration Appeals decision granting asylum to a Salvadoran woman fleeing her husband.

U.S. officials do not say how many asylum claims are for domestic or gang violence, but advocates for asylum seekers said there could be tens of thousands of such cases in the immigration court backlog alone. Many Central Americans seeking asylum say they are fleeing from gangs known as “maras,” primarily the Mara Salvatrucha (or MS-13) and Barrio 18 groups. President Donald Trump has condemned those groups and the violence they commit in the U.S., referring to members as “animals.”

The gangs were formed by young Central Americans mostly in Los Angeles decades ago and spread to the so-called Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras when members were deported. Today, Honduras and El Salvador in particular routinely post some of the world’s highest homicide rates. In Central America, maras stake out and battle over turf, attacking anyone who unwittingly crosses through their area on the way to school or work as a possible rival. Gangsters sometimes forcibly take over people’s homes. They extort bus drivers and small business owners, killing those unable or unwilling to pay. They threaten teens and young men in attempts to recruit them, and force girls and young women to be their girlfriends.

Maureen Meyer, director for Mexico and migrant rights at the Washington Office on Latin America advocacy group, said the ruling would “make it very difficult for a lot of the people seeking asylum in the United States.” Meyer said Central Americans commonly request asylum for extortion, forced recruitment and violence against women. Where the gangs are prevalent, moving elsewhere is not an option, she said. “People feel very insecure in their homes and continue to see the U.S. as a safe haven in spite of Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric,” Meyer said of the steady northbound flow of Central Americans that began in 2014.

More than 100 asylum seekers gathered Wednesday near the entrance to San Diego, the largest crossing on the U.S.-Mexico border. Some Mexicans in the crowd said they were fleeing criminal groups. Holding her 7-month-old daughter and trailed closely by her 5-year-old son, who was on crutches because of a gunshot wound, Maria Rafaela Plancarte said she abandoned their town near the western Mexican city of Zamora after her husband was shot and killed behind the wheel of the family car as they fled a party stormed by gunmen. Her son was wounded in the attack. Plancarte, 34, said she has not considered moving elsewhere in Mexico and hopes to live with an aunt in California. “I will feel more comfortable with a family that I know,” she said.

Alejandro Arroyo said he fled Apatzingan in western Mexico with his wife and their 14-year-old son, hoping asylum would bring them to his wife’s family in Gilroy, California. The 48-year-old said criminal gangs killed his nephew and brother-in-law, and he feared he and his son would be next. They initially sought refuge in Tijuana, but requested U.S. asylum after being robbed by local police. “I do not feel safe” in Apatzingan, Arroyo said, “and I do not feel safe here.”

Jose Osmin Aparicio, from El Salvador, is caught in the middle of the change in asylum policies. His wife requested asylum about a month ago with three of their children – ages 2, 10 and 12 – and they were released to a family in Maryland while their cases wind through immigration court. Aparicio stayed in Tijuana to seek asylum with his 17-year-old son, hoping to reunite with the family later. Sessions subsequently made his ruling on gang violence, but Aparicio is still pursuing asylum and hopes to get into the U.S.

No Comment