Modern Motherhood Has Economists Worried

(Bloomberg) —Motherhood is changing, as are mothers’ working lives—and those changes have economists concerned.

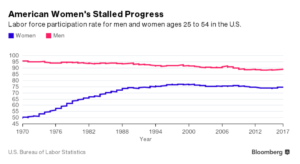

For a while, women around the world were making clear economic progress. More of them were working, and they were earning more (and boosting the global economy in the process).

But in the past few decades, that progress has stalled. Women’s participation in the U.S. workforce peaked two decades ago. And today, women are making big changes to when, and whether, they have children.

Economists have begun paying attention. Last week, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen raised the alarm in a speech at Brown University. “We, as a country, have reaped great benefits from the increasing role that women have played in the economy,” she said. “But evidence suggests that barriers to women’s continued progress remain.”

Among those barriers: “a lack of equal opportunity and challenges to combining work and family.”

Since the demands of parenting are a key factor keeping women out of the workforce, Yellen and other economists are focusing on the barriers that parents, especially mothers, face—among them the high cost of child care and a lack of workplace flexibility. “To keep women and men productive in the labor market, it is a good idea to have supporting institutions that can ease some of the burdens of both single parents and married couples with children,” said Torsten Slok, chief international economist at Deutsche Bank.

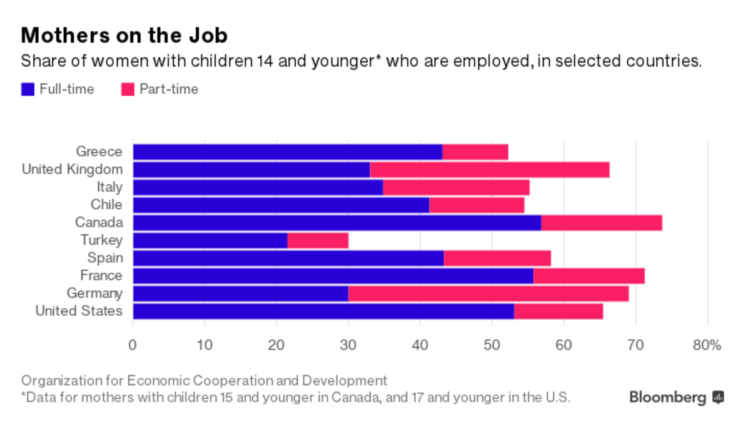

For now, though, women around the world are much less likely than men their age to be employed—and American women are less likely than women in many European countries to work.

Those gaps carry an economic cost, for women as well as for the U.S. and global economies.

From 1948 to 1990, the surge of women into the workforce boosted the U.S. economy’s potential growth rate by 0.5 percentage points each year, Yellen said in her speech. Other research suggests the U.S. economy would expand 5 percent if as many women were employed as men. Japan’s would increase 9 percent, and Egypt’s 34 percent.

That’s growth the world can’t spare at a time when other factors, such as aging populations and low productivity increases, are holding economies back.

A unique factor facing American mothers is the U.S.’s lack of paid maternity leave. Almost every developed country guarantees mothers paid time off when they have a child. On average, the 35 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development (OECD) offer 18 weeks of paid leave. The U.S. guarantees none.

Almost everywhere, women are waiting longer to have children. In 2015, the average age at which American mothers had their first child was 26.4—up from 22.7 a generation before, in 1980. That age has risen even faster for women elsewhere. The oldest new moms, according to a study earlier this year, are in South Korea, where the average women is 31.1 when she has her first child.

Motherhood affects women’s careers in varying ways, depending on their occupations. A 2014 study found about a quarter of American mothers of preschoolers don’t work. Women in managerial or professional jobs were the most likely to remain in the workforce: Only 15 percent of them stopped working while their children were young—but they did cut back on how much they worked, by about 2.5 hours per week, on average. (A Pew Research Center survey released in March found that American workers in households making more than $75,000 a year are twice as likely to get paid leave as those whose households earn less than $30,000.)

Not all women have children, of course. But the vast majority do: Only 14.4 percent of American women age 40 to 44 have never given birth, a number that’s fallen from a peak of 20.4 percent in 2006. At the same time, however, women are waiting longer and longer to have their first child. In the U.S., 31 percent of women age 30 to 34 had never given birth to a child, according to 2016 Census data. That’s up from 26 percent in 2006.

By still having kids but having them later, women find their careers are changing in significant ways.

“A new life cycle of women’s labor force participation has emerged,” Harvard University professor Claudia Goldin and U.S. Census researcher Joshua Mitchell found in a recent study. Women in the U.S. participate in the workforce at high rates in their 20s—but fewer of them are working in their 30s and early 40s, a time Goldin and Mitchell call “the sagging middle.”

That time out of the workforce interrupts peak earning years for women, particularly mothers; for the rest of their careers, perhaps once their kids are older, they must make up for lost time and money. The number of women working well into their 60s and 70s has surged in the U.S., as more of them postpone retirement.

Have personal finance questions or lessons to share? Join Money Talks, the new Facebook community from Bloomberg News.

No Comment