Dark Matter – Something’s Not Right Here : A Well Thought Out Scream by James Riordan

For years now we’ve been hearing about “Dark Matter”. According to Wikipedia “Dark matter is an unidentified type of matter comprising approximately 27% of the mass and energy in the observable universe[1] that is not accounted for by dark energy, baryonic matter (ordinary matter), and neutrinos.[2] The name refers to the fact that it does not emit or interact with electromagnetic radiation, such as light, and is thus invisible to the entire electromagnetic spectrum.[3] Although dark matter has not been directly observed, its existence and properties are inferred from its gravitational effects such as the motions of visible matter, gravitational lensing, its influence on the universe’s large-scale structure, and its effects in the cosmic microwave background. Dark matter is transparent to electromagnetic radiation and/or is so dense and small that it fails to absorb or emit enough radiation to be detectable with current imaging technology.”

Got that?

Let me try and simplify. Dark Matter is the stuff we know is there but we can’t see. That could be anything from invisible rays and energy that we haven;r figured out how to identify yet to angels and demons. That’s right. We jow something is there but we don’t know what it is. It could be the things that go bump in the night or the glue that keeps this whole ball of wax rolling down the highway — so to speak. Here are some photos and tidbits.

Since the 1930s, scientists have known that there was something unexplained about the heavens. Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky studied the Coma Cluster, a group of about a thousand galaxies, held together by their mutual gravitational interactions. There was only one problem: The galaxies were moving so fast that gravity shouldn’t have been able to hold them together. The cluster should have been ripped apart. In the 1970s, astronomers Vera Rubin and her collaborator Kenneth Ford studied the rotation rates of individual galaxies and came to the same conclusion. There appeared to be no way the observed matter contained in galaxies would generate enough gravity to keep the stars locked in their stately orbits.

These observations, combined with many other independent lines of evidence, led scientists to consider several possible explanations. These explanations included the possibility that Newton’s familiar laws of motion might be wrong, or that our understanding of gravity needed to be modified. Both these proposals, though, have been largely ruled out.

Another idea was that there was somehow invisible matter that was generating more gravity. Initial ideas centered on the possibility of black holes, brown dwarf stars or rogue planets roaming the cosmos, but those explanations have also been dismissed. Using a ruthless process of elimination worthy of Sherlock Holmes, astronomers have come to believe the explanation for all of the gravitational anomalies is that there must be some sort of new and undiscovered type of matter in the universe, which Zwicky in 1933 named “dunkle materie,” or dark matter.

For decades, scientists have tried to work out the properties of dark matter and, while we don’t know everything, we know a lot. From astronomical observations, we know there is five times more dark matter in the universe than all the “billions and billions” of stars and galaxies mentioned in Carl Sagan’s oft-quoted phrase. We also know that dark matter cannot have electrical charge, otherwise it would interact with light and we would have seen it. In fact, by a process of elimination, we know that dark matter is not any known form of matter. It is something new. Of this, scientists are sure.

However, scientists are less sure about the details.

For decades now, the most popular theoretical idea was that dark matter was a WIMP, short for weakly interacting massive particle. A WIMP would have a mass in the range of 10 to perhaps 100 times heavier than the familiar proton. It was a particle like a heavy neutron (but definitely not a neutron), massive, electrically neutral, and stable on time scales long compared to the lifetime of the universe.

The WIMP was popular for two main reasons.

First, when cosmologists modeled the Big Bang and included WIMPs in the calculation, the WIMPs actively participated in the earliest phases of the birth of the universe but, as the universe expanded and cooled, the space between them grew large enough that they stopped interacting with one another. When scientists calculated how much mass should be tied up in the relic WIMPs, they found it was five times as much mass as ordinary matter, exactly the amount of dark matter seen by astronomers.

Three years ago, scientists in Geneva, Switzerland, announced they had proved the existence of the so-called “God particle” known as Higgs boson — a never-before-seen subatomic particle long thought to be a fundamental building block of the universe. This year, researchers from two different teams combined their measurements of the particle, providing an unprecedented picture of Higgs boson’s production, decay and interaction with other particles.

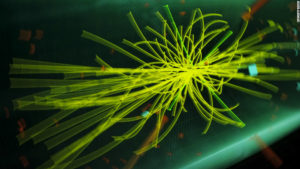

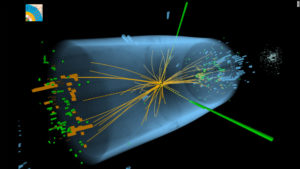

This graphic shows traces of the collision of particles from an experi ment at the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) — a large particle detector in Geneva. The Standard Model of particle physics lays out the basics of how elementary particles and forces interact in the universe. But the theory crucially fails to explain how particles actually get their mass. Particles, or bits of matter, range in size and can be larger or smaller than atoms. Electrons, protons and neutrons, for instance, are the subatomic particles that make up an atom. Scientists believe that the Higgs boson is the particle that gives all matter its mass.

ment at the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) — a large particle detector in Geneva. The Standard Model of particle physics lays out the basics of how elementary particles and forces interact in the universe. But the theory crucially fails to explain how particles actually get their mass. Particles, or bits of matter, range in size and can be larger or smaller than atoms. Electrons, protons and neutrons, for instance, are the subatomic particles that make up an atom. Scientists believe that the Higgs boson is the particle that gives all matter its mass.

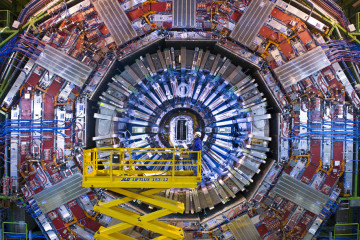

An image of the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment. “The Higgs boson is the last missing piece of our current understanding of the most fundamental nature of the universe,” Martin Archer, a physicist at Imperial College in London, told CNN. “Only now with the LHC [Large Hadron Collider] are we able to really tick that box off and say ‘This is how the universe works, or at least we think it does’.”

An image of the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment. “The Higgs boson is the last missing piece of our current understanding of the most fundamental nature of the universe,” Martin Archer, a physicist at Imperial College in London, told CNN. “Only now with the LHC [Large Hadron Collider] are we able to really tick that box off and say ‘This is how the universe works, or at least we think it does’.” Higgs boson research takes place at the Large Hadron Collider — a circular tunnel located 100 meters (328 feet) underground. It uses a particle accelerator to collide protons at extreme speeds. By combining their data, researchers found that there are different ways to produce a Higgs boson, and different ways for a Higgs boson to decay to other particles.

Higgs boson research takes place at the Large Hadron Collider — a circular tunnel located 100 meters (328 feet) underground. It uses a particle accelerator to collide protons at extreme speeds. By combining their data, researchers found that there are different ways to produce a Higgs boson, and different ways for a Higgs boson to decay to other particles.

British physicist Peter Higgs (R) speaks with Belgium physicist Francois Englert at a press conference on July 4, 2012 at European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) offices in Meyrin near Geneva. After a quest spanning nearly half a century, physicists said on July 4 they had found a new sub-atomic particle consistent with the Higgs boson which is believed to confer mass. Rousing cheers and a standing ovation broke out at the CERN after scientists presented data in their long search for the mysterious particle.

British physicist Peter Higgs (R) speaks with Belgium physicist Francois Englert at a press conference on July 4, 2012 at European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) offices in Meyrin near Geneva. After a quest spanning nearly half a century, physicists said on July 4 they had found a new sub-atomic particle consistent with the Higgs boson which is believed to confer mass. Rousing cheers and a standing ovation broke out at the CERN after scientists presented data in their long search for the mysterious particle.

Teams from ATLAS and CMS Collaborations combined their research to obtain their results. “Combining results from two large experiments was a real challenge as such analysis involves over 4,200 parameters that represent systematic uncertainties,” said CMS Spokesperson Tiziano Camporesi. “With such a result and the flow of new data at the new energy level at the LHC, we are in a good position to look at the Higgs boson from every possible angle.”

Teams from ATLAS and CMS Collaborations combined their research to obtain their results. “Combining results from two large experiments was a real challenge as such analysis involves over 4,200 parameters that represent systematic uncertainties,” said CMS Spokesperson Tiziano Camporesi. “With such a result and the flow of new data at the new energy level at the LHC, we are in a good position to look at the Higgs boson from every possible angle.”

The particle accelerator magnets of the LHC are shown at the underground test facility at CERN near Geneva. Many scientists dislike the term “God particle,” even though it’s become popular in the media. The nickname came from the title of a book by Leon Lederman, who reportedly wanted to call it the “Goddamn Particle” since it was so hard to find.

In the preface to a 2014 book, astrophysicist Stephen Hawking wrote he was worried that Higgs boson might turn unstable and lead to the end of everything. The “universe could undergo catastrophic vacuum decay, with a bubble of the true vacuum expanding at the speed of light,” Hawking wrote. “This could happen at any time and we wouldn’t see it coming.” Not to worry too much. Hawking added that such a scenario would require a “particle accelerator that … would be larger than Earth, and is unlikely to be funded in the present economic climate.”

In the preface to a 2014 book, astrophysicist Stephen Hawking wrote he was worried that Higgs boson might turn unstable and lead to the end of everything. The “universe could undergo catastrophic vacuum decay, with a bubble of the true vacuum expanding at the speed of light,” Hawking wrote. “This could happen at any time and we wouldn’t see it coming.” Not to worry too much. Hawking added that such a scenario would require a “particle accelerator that … would be larger than Earth, and is unlikely to be funded in the present economic climate.”

1 Comment

You have written a clear and concise exposition of what we know and don’t know about this strange stuff. I like the fact that a lay person can understand it.

Have you noticed that every time we make a scientific advance in this field and gain a new understanding, the new knowledge is more difficult to grasp (less intuitivly clear) than our previous understanding and raises more difficult questions? Advances used to be made by observing the world and then forming mathematcal models (e.g., Keppler and Newton) but now are made by pure mathematics (abstract to the point where few can understand them – Einstein and Hawking) and sometimes it take decades to confirm them with observation. Those who grasp this math say it is like getting a glimpse of the mind of God.